ABSTRACT

Economic suffering prompted by the Covid-19 pandemic, coming on the heels of earlier 2008 global-financial and 2015 migration crises, revived debate on citizen support for European fiscal integration policies. Such support can be expected to reflect not only individual-level characteristics but also the extent of crisis exposure in subnational regional contexts where individuals live and work. Unfortunately, existing studies of public support have said little about such regional contexts. This study hence explores how regional-level experience with ‘polycrisis’ affects support for EU fiscal capacities, combining regional-level crisis measures with a 2020 survey experiment on European citizens’ preferences towards fiscal capacity instruments in 5 European countries (DE, ES, FR, IT, NL). This allows tests of whether individual support for various European fiscal capacities reflect regional differences in covid suffering, growth losses after the 2008 global financial crisis, and migration spikes from the 2015 migration crisis. We expect and find that citizens in regions more heavily impacted by the pandemic, financial crisis, and (albeit less so) migration crisis – measured separately and as a composite – tend to more readily support European fiscal integration capacity that is redistributive between countries, financed through progressive taxation, refrains from budgetary conditionality, and is lenient towards reform non-compliance.

Introduction

Major crises hitting European member polities have uncertain implications for European Union (EU) integration, including public support for broad fiscal capacities of the EU. On the one hand, the Europe-wide or global reach of the crises pose shared patterns of suffering that can fuel political mobilisation into larger, winning coalitions within and between member states to support expanding EU capacities to collectively address crises. On the other hand, jointly-felt crises impact people, regions and countries differently, sparking different, conflicting, mobilisation of preferences and proposals that can yield ‘constraining dissensus’ and ‘negative politicisation’ within and between countries that undermine rather than deepen EU capacities (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2009; De Wilde, Citation2012; Schimmelfennig, Citation2018, Citation2019; Ferrara & Kriesi, Citation2022). Such offsetting implications are complicated enough for a given crisis, but they are even more uncertain with what can be called Europe’s polycrisis (Zeitlin et al., Citation2019): at the time of this writing potentially involving some combination of the post-2008 financial and debt crisis, the post-2015 migration crisis, the 2020s Covid-19 crisis, and the post-2022 energy and security crisis surrounding the Russia-Ukraine war. Perhaps cumulation of these crises fosters broader, deeper coalitions to pool sovereignty through EU capacities. Or perhaps multiple crises simply foster more dissensus created by different distributional consequences emerging from disparate crises – that cripple rather than cumulate support for European Union capacities.

The substantial literature on public opinion towards EU fiscal capacities or integration helps clarify crisis-led politicisation, but only partially. In particular, studies have not yet taken sufficient account of two features of how polycrisis can be expected to affect support for or opposition to EU fiscal capacities. First, most surveys have focused on a given crisis rather than multiple crises – for instance, either the financial crisis (e.g., Serricchio et al., Citation2013), or the asylum-migration crisis (e.g., Hobolt & Wratil, Citation2015; Stockemer et al., Citation2020), or the Covid-19 crisis (e.g., Bobzien & Kalleitner, Citation2021; Bremer et al., Citation2023). This makes it difficult to know whether and how exposure to multiple crises at play at a given survey moment plays out for attitudes and conflict. Second, most studies addressing crisis and opinions about EU capacities have focused on individual- or country-level characteristics, or more general timing of surveys or individual attitudes about a crisis (e.g., about covid worry or exposure) (e.g., Krehbiel & Cheruvu, Citation2021; Beetsma et al., Citation2022). These say little about crisis exposure felt at the regional level where an individual resides. This neglects a layer of crisis politicisation that can strongly shape reasoning about crisis and the EU, and can differ in character and effects from individual and country-level experience. In short, existing studies have not well captured how multiple crises and the regional level of crisis experience can shape attitudes towards EU capacities.

This paper explores how polycrisis affects individual attitudes towards EU fiscal capacities, taking explicit account of the role played by regional-level measures of exposure to multiple crises prevailing during our study’s survey period (early 2020) – particularly Covid-19-related mortality and infections, but also drop in regional GDP growth after 2008 and regional increase in migration surrounding the 2015 migration shock. While each crisis might have distinct implications, and while a given region might be differently affected by different crises, we expect regional-level crisis measures to share three key implications for residents: to spark individual economic insecurities, to strain local fiscal capacities, and thereby to render residents of more impacted regions to be expected net beneficiaries of expanded EU fiscal capacity. As a result, we expect that each regional crisis measure and measures of their combination should spur support for such capacity generally, and for more redistributive and permissive EU fiscal capacity in particular. We expect such effects to show-up net of an individual’s socio-economic position and risks – with regional experience therefore capturing a distinct layer of crisis politics.

Our empirical exploration relies upon an original survey experiment gauging support for new EU fiscal capacities. We explore the possible effects of regional-based exposure to crises by using information about a respondent’s (NUTS-2Footnote1) residence, measured in addition to information about a respondent’s individual socio-economic position. The survey was carried out in early 2020, the beginning of the Covid-19 crisis, particularly suited to exploring possible effects of the Covid-19 crisis. But our NUTS-2 coding allow us to consider the possible effects also of two other previous but still salient crisis experiences – a region’s exposure to the 2008 financial/budget crisis and to the 2015 migration crisis. Our analysis estimates how regional-based measures of exposure – to Covid-19 mortality and infection, to migration rates post- vs. pre-2013, to GDP and employment loss post- vs. pre-2008, or to combinations of these measures – alter support for (randomly shown) design features of EU fiscal capacity (e.g., more or less redistributive or punitive design). These analyses consider how such regional crisis experience separately or in combination has implications for support for EU fiscal capacities net of individual-level socio-economic risks (e.g., low income, low education, etc.).

The analysis provides partial support for our expectations. On the one hand, among the region-based measures of crisis, only Covid-19 exposure (measured as weekly excess mortality rates) statistically-significantly increases a European voter’s probability of supporting EU fiscal capacity generally – averaging across all fiscal policy combinations with respect to redistribution, conditionality, and punitiveness. On the other hand, the region-based crisis measures, particularly with respect to covid exposure and post-2008 GDP loss (more than regional migration impact), tend to increase the probability of supporting EU fiscal capacity that is more redistributive between countries, more redistributive in tax burden, less conditional on budget probity, and less punitive for fiscal noncompliance. These patterns suggest that regional-based exposure to the relevant manifestations of polycrisis – net of individual-level experience – may not so much increase support for EU fiscal capacity generally, but instead for more redistributive and permissive capacity.

Theories and argument: regional crises and EU fiscal capacities

To better understand how crises play out for EU politicisation, we build on existing literature exploring public opinion and voter mobilisation on issues of EU fiscal integration or capacities. That literature sheds substantial light on how political-economic crises facing European Union member states can lead to voter support and opposition to key aspects of European integration. They do so by clarifying the socio-economic predictors of support or opposition to European integration and capacities – including most obviously the individual material interests of voters (jobs, wealth, etc.), beliefs about the functioning of economic and political life, and normative commitments to equality, efficiency, fairness, etc. Such micro-level information is key to politicisation in EU member-state democracies. Most obviously, the cleavages shaping EU support or opposition identify wants of voters manifesting either ‘positive politicisation’ or ‘negative politicisation’ of European integration – where positive politicisation involves political contestation and coalitions supporting EU capacities, and negative politicisation involving contestation and coalitions against such capacities.

What polycrisis has to do with such politicisation has been construed in many ways, including in this Special Issue (Nicoli & Zeitlin, Citation2024). Minimally, polycrisis means the simultaneity or combination of multiple crises at a given point in time (Zeitlin et al., Citation2019). For many scholars, however, polycrisis means more than such simultaneity of problems (Morin, Citation1999; Davies & Hobson, Citation2023; Tooze, Citation2021). Junker’s (Citation2016) speech using the term spoke of challenges that are not only simultaneous but ‘ … also feed upon each other, creating a sense of doubt in the minds of our people’ (Citation2016, p. 1). Davies and Hobson (Citation2023), provide among the more extensive conceptualizations, discussing eight features of polycrisis: multiplicity; feedback loops; amplification; unboundedness; layering; breakdown of shared meaning; cross-purposes; emergent properties (reflexivity) (p. 160). Surely these features are more or less relevant to some crisis moments and to some policy-political interactions and not others. So the meaning and causal importance of (one or another aspect of) polycrisis to EU integration politics is likely to be strongly dependent upon the particular multiple crises involved and upon the aspect(s) of EU integration being debated.

Amidst diverse conceptions of EU politization and crises, the existing corpus of public opinion studies of EU integration clarifies how (aspects of) polycrisis might politicise such integration. Survey-focused scholarship has explored many economic and political/cultural conditions, often explicitly manifesting crises, that are relevant to positions on EU integration (e.g., Gerhards et al., Citation2019). This includes attention to how individual material interests – income, education, employment status, income position, exposure to trade or investment, or migration – shape support for EU capacities (e.g., Gabel & Palmer, Citation1995; Kuhn et al., Citation2016; etc.). Another body of work has focused on country-level conditions that shape attitudes towards EU integration – including how national-level wealth, net benefits from EU budgets, trade exposure, social policy orientation, migration exposure, inequalities, etc. shape support for EU capacities (e.g., Anderson & Reichert, Citation1995; Carrubba, Citation1997; Sánchez-Cuenca, Citation2000; Eichenberg & Dalton, Citation1993; Hooghe & Marks, Citation2005). A more relevant but smaller literature explicitly explores how public opinion towards EU integration and capacities reflects individual and country-level experiences with particular crises, such as: the global financial crisis (Tosun et al., Citation2014; Serricchio et al., Citation2013); the refugee crisis (e.g., Hobolt & Wratil, Citation2015; Di Mauro & Memoli, Citation2021; Stockemer et al., Citation2020); and the Covid-19 crisis (e.g., Bobzien & Kalleitner, Citation2021; Bremer et al., Citation2023; Heermann et al., Citation2023; Krehbiel & Cheruvu, Citation2021; Beetsma et al., Citation2022).

These studies paint a mixed picture of voter stances or disagreements, or other manifestations of negative or positive politicisation. The pieces explore individual-level and country-level forces shaping EU politicisation, but they do not resolve whether (a given) political economic crisis fosters, in the net, more negative than positive politicisation. For instance, studies exploring the role of poverty or economic vulnerability in country-level dynamics yield competing patterns with respect to the direction of politicisation of EU integration. Some studies, for instance, have found evidence that poorer and more vulnerable countries tend to be more supportive of EU integration and fiscal capacities (e.g., Anderson & Reichert, Citation1995; Carrubba, Citation1997; Eichenberg & Dalton, Citation1993; Hooghe & Marks, Citation2005; Vandenbroucke et al., Citation2018; Burgoon et al., Citation2022). Others, however, have found that (pre-covid era) national-level misfortune, including being more impacted by macroeconomic crises (e.g., austerity), often spurred EU skepticism (Chalmers & Dellmuth, Citation2015; Kleider & Stoeckel, Citation2019; Kuhn et al., Citation2018; Lengfeld et al., Citation2015). And some studies find that national-economic experiences moderate the effects of individual characteristics on support for EU integration or solidarity (Mariotto & Pellegata, Citation2023; Vasilopoulou & Talving, Citation2020).

Whatever the paths to synthesising such discordant findings, two shortcomings stand in the way of understanding how polycrisis plays out for EU politicisation. First, existing public-opinion studies have done little to tackle multiple, consecutive or overlapping crises that European member states sometimes face. As revealed by the discordant patterns on how national-level struggles affect support for EU prerogatives, the links are different across crises and periods. The immediate aftermath and later struggles to deal with the financial crisis played out very differently – with macro-level political economic struggles initially playing out more towards euroskepticism – whereas the polities and individuals more struggling with covid and in its ongoing aftermath have yielded substantially more pro-EU capacities. The aftermath of the refugee crisis between 2013 and 2016 has played out somewhere in between – where national-level exposure does not seem to significantly alter support for integration (Stockemer et al., Citation2020). Such differences across crises remind us that one crisis can play out very differently than another. Indeed, the distributional consequences of the global financial crisis were and are different than those of the covid pandemic, and both are different than the distributional consequences of the refugee crisis. But it is also a reminder that a crisis felt and acted upon at any given moment may be more or less recent, and crisis implications do not just reflect the most recent crisis but perhaps also learning from or simmering effects of earlier other crises (Seabrooke & Tsingou, Citation2019; Zeitlin et al., Citation2019). Understanding how polycrisis might shape EU politicisation, hence, requires attention to multiple crises – as difficult as this may be with (pricey) survey instruments.

Second, existing studies have tended to undertheorize the regional-, community-level of socio-economic exposure to crisis that can distinctly affect politicisation beyond individual or national-level exposure. As we have seen, some opinion studies on fiscal capacities have considered national-level experience in addition to individual-level experience – some finding that people in net-recipient member states are more favourable towards more redistributive, generous, and less conditional fiscal programs (Bremer et al., Citation2023; Vandenbroucke et al., Citation2018; Beetsma et al., Citation2022). And yet, citizens are also directly impacted by and aware of their more local socioeconomic situation compared to generalised, average situation of the nation (Kirman, Citation2010; Reinl et al., Citation2023; Stockemer, Citation2016). Some public-opinion studies do address such regional-level experience and support for European integration. Some such studies have found more euroskepticism among residents of regions more exposed to import shocks (Colantone & Stanig, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Nicoli et al., Citation2022), regions in low-income and high unemployment regions (Dijkstra et al., Citation2020; Lechler, Citation2019; Nicoli & Reinl, Citation2020), regions less compensated through EU regional funds (Schraff, Citation2019), and regions with low over-time regional growth (Vasilopoulou & Talving, Citation2023). But such findings focus on general trust or support for the broad integration project, not support for actual, named EU capacities. An exception links regional-level measures of economic wealth to support for EU social policy capacities, where those in poorer regions tend to be more supportive of EU social provision that is redistributive and less conditional on activation measures (Reinl et al., Citation2023). Even here, however, regional-level economic wealth can be expected to have different effects than regional exposure to actual crisis dynamics, and EU social policy may well be judged differently than broad EU fiscal capacity.

Argument: regional-level crises and support for EU fiscal capacity in 2020

To clarify how polycrisis shapes EU political contestation, we focus on how regional-level exposure to multiple crises salient in early 2020 can shape individual voter support for (particular kinds of) EU fiscal capacity. Our specific expectations build on two broad arguments about what existing scholarship tends to leave out: how regional-level exposure matters, and how multiple crises play out as polycrisis.

First, crises are experienced through and acted upon partly in light of not just a person’s country or individual traits and endowments, but also of regional-level crisis conditions in which individuals live. Regional settings can shape a resident’s political positioning through both egoistic reasoning about his or her own risk and socio-tropic reasoning about his or her broader community. This is something considered in many political economy realms (e.g., Mansfield & Mutz, Citation2009; Kinder & Kiewiet, Citation1981; Sears & Funk, Citation1990; Kramer, Citation1983). Regional features can spark egoistic reasoning by proxying through region membership a resident’s own interest (i.e., environmental heuristic cues). Regional features spark socio-tropic reasoning, in contrast, through some combination of in-group altruism or self-interests dependent on the community’s well-being (Schaffer & Spilker, Citation2019). Regional experience can therefore capture also broadened self-interest that is not always strictly utilitarian in nature, but also entails ‘cue-taking’ and ‘identity’ (in the terminology of Hobolt & de Vries, Citation2016). Also, regional experience can reflect both subjective perceptions (concerns about the state of one’s region) and objective phenomena (the state of one’s region). The former, subjective concerns may be more proximate political motivators, but they may well be preceded by more exogenous context in opinion formation (Hansford & Gomez, Citation2015; Jungherr et al., Citation2018; Song & Bucy, Citation2008). In our conceptualisation, regional context can matter through any of these reasoning mechanisms.

Second, how multiple crises play out as polycrisis is very much context-dependent with respect to both the particular crises that are salient and with respect to aspects of EU policymaking at play. The sub-crises constituting polycrisis of a given moment can differ with respect to what and whose interests and ideas are affected by the crisis, with such implications in turn differing across particular aspects of European politics or policy. For instance, plenty of crises have strong distributional consequences in economic terms, as holds for financial/budget crises; other crises, however, have more muted distributional consequences, such as the recent Ukraine security crisis (manifesting more nationally uniform security implications, despite uneven energy- or sanction-implications). Crises with clear and uneven economic implications across regions, further, can be expected to have distinct, potentially offsetting implications for particular occupations, sectors or regions. And different crises can be more or less overwhelming as ‘focusing events’ (DeLeo et al., Citation2021), ‘fast-burning’ or ‘slow-burning’ (Seabrooke & Tsingou, Citation2019), more or less enduring or ‘creeping’ in their effects (Boin et al., Citation2020; Zaki, Citation2023). Such wide-ranging crises also can matter differently for different policy realms – for instance being different for European policies with respect to social policy, health, immigration, or environment, or for broader fiscal capacities and rules of governance. In our conceptualisation, ‘polycrisis’ has meaning only once one can specify the crisis and policy context under review.

The particular context of polycrisis on which we focus involves support for general EU fiscal capacities and three distinct crises prevailing in early 2020. EU fiscal capacity has been for many years among the most important and salient frontiers of European integration. And for the early 2020 period of our data, three crises loomed more or less largely and simultaneously: most salient was the ongoing first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic; but in clear memory were two other, quite different, crises, the post-2008 financial/budget crisis and the 2015 migration crisis. The regional contexts on which we focus are a person’s region of residence and work captured by the NUTS-2 level that broadly coincides with the parlance of a province. We focus on measures that gauge the severity of the three crises experienced in such NUTS-2 regions: severity of the Covid-19 pandemic (e.g., excess mortality or infection rates at the time of the survey), severity of loss from the global financial crisis (e.g., drop in provincial GDP or employment since 2008), and severity of the ‘2015 refugee crisis’ amidst the Syrian Civil War (e.g., net migration between 2013 and 2016).

These three regionally-gauged crises can certainly be expected to be distinct in their implications for attitudes about EU fiscal capacities. Most obviously, one crisis being in the first instance a health crisis, another a broader financial/budgetary economic crisis, and the third being a crisis of demographic composition – each potentially touching different political and economic interests and volition. And given the timing and severity of the pandemic relative to the early-2020 fielding of our survey, covid severity can certainly be expected to matter most to any political calculations about European integration, including EU fiscal capacity.

However, all three crises share important economic implications that we expect should play out in similar directions with respect to debates and political contestation about EU fiscal capacity. First, all three crises experienced at the level of regional severity pose threats to a person’s economic security. Second, all three crises can also be expected to strain existing local fiscal capacities in the affected regions concomitant to the severity of the crisis experienced. And third, given these two implications, all three crises can be expected to render individuals living in more severely-impacted regions to be expected net beneficiaries of enhanced EU fiscal capacity generally, and of more redistributive and lenient fiscal capacity in particular.

The ways that these three implications can be expected to manifest themselves for the three crises do differ somewhat and hence deserve attention. For the Covid-19 crisis, people in regions with higher region-specific infection rates or (excess) mortality rates can be expected to not only suffer more in their basic health outcomes but also face heavier losses in higher unemployment and lower regional GDP growth (Přívara, Citation2022; Ortenzi et al., Citation2020) and household income loss (Almeida et al., Citation2021). Such patterns can be expected to make residents worry about their own livelihood (e.g., job loss) and that of their communities (Ibanescu et al., Citation2023). This putative link between regional pandemic severity and subsequent economic insecurity contrasts sharply with findings that ex ante GDP per capita predicts stronger health outcomes and infrastructure that might undergird severity of the first wave (Amdaoud et al., Citation2021). Whatever the implications for one’s own or one’s community’s economic security, regional-level pandemic severity also has been found to put substantial strain on regional healthcare and social services and hence fiscal position (Androutsou et al., Citation2021). Finally, these implications for economic insecurity ad fiscal strain can make residents of more severely-hit regions net beneficiaries of enhanced EU fiscal capacities, particularly those quickly on the agenda in early 2020 (e.g., SURE, RRF, medicine and procurement capacities).

For the second crisis – the lingering economic losses from the post-2008 global financial/budget crisis – the story is similar. Those in the more severely impacted regions in post-2008 drop in provincial GDP can see worse economic insecurity with respect to job or income worry for themselves or their community (Alessi et al., Citation2020; Nicoli & Reinl, Citation2020; Colantone & Stanig, Citation2018a). Separate from this, larger provincial GDP drops also substantially strain provincial public bureaucracies and institutions (e.g., Palasca & Jaba, Citation2015). Such double implications again should render those in more finance-crisis impacted regions more likely to be net beneficiaries than net contributors of enhanced EU fiscal capacity.

As for the third, 2015 migration crisis, the implications for economic insecurity, fiscal strain and net beneficiary status with respect to EU fiscal capacities are less straight-forward. Those regions experiencing higher increases in post-2013 net migration have uncertain implications for economic insecurities of their residents. On the one hand, the migration influx captured by such conditions might entail medium-term labour-market competition for some residents, particularly in the longer run (Mayda, Citation2006; Scheve & Slaughter, Citation2001). There’s some evidence that the asylum-crisis migrants tended to have lower educational attainment than earlier migrants to Europe (Dumont et al., Citation2016), and that provincial-level low-skilled net migration is associated with increases in regional unemployment in host settings (Basile et al., Citation2019). On the other hand, there’s also some evidence that regional-level migration patterns bring net employment and growth benefits at the regional level, at least in the long term, particularly with respect to the high-skilled component of migration waves (e.g., OECD, Citation2022; Basile et al., Citation2019). And the particular 2015 asylum-seeker migration has as-yet unexamined short- and medium-term regional economic implications. This makes the implications for direct economic insecurities unclear.

With respect to implications for fiscal strain, however, the implications for existing public services are substantial – not just the disproportionate net-beneficiary status of migrants posing strain on non-contributory social protections and other services (Hanson et al., Citation2007; Boeri, Citation2010), but also more concentrated fiscal strain of hosting, housing and integrating asylum seekers (Goodman et al., Citation2017). These two sets of implications – ambiguous with respect to resident economic insecurity and clear-cut fiscal strain – still imply at least qualified net beneficiary status for residents from enhanced EU fiscal capacity, particularly capacities shoring up national or local resources for migrant integration and labour market risks.

Still, what is particularly distinct about the migration crisis compared to the other two crises is that the political economic mechanisms focused-upon here might pale in comparison to many cultural considerations, including racial, ethnic and national identity concerns awakened by high regional net migration (Colantone & Stanig, Citation2018; Czaika & Di Lillo, Citation2018; Häusermann & Kriesi, Citation2015; Dustmann & Preston, Citation2007; Sides & Citrin, Citation2007; Stockemer et al., Citation2018, Citation2020). These cultural considerations may raise concerns about deservingness and support for welfare chauvinism that can colour the character of or hold-back expanded EU capacities (Hjorth, Citation2016; Reeskens & Van der Meer, Citation2019). And they can more generally unleash nationalist reaction and suspicion that EU fiscal capacities pose danger – even if one is rendered in an expected net beneficiary position with respect to such capacities.

Despite such differences in how crises play out, a focus on the political-economic implications suggests that all three crises can be expected to spur economic insecurities, strain public services and fiscal positions, and thereby foster expected net benefits of EU-level fiscal capacities. If so, then residents of crisis-impacted regions can be expected to be aware of that experience, given widespread discussion of the various crises. This can obtain even if some of the residents some of the time misattribute their region’s pain to influences other than their region’s crisis exposure (Wu, Citation2022). The period of our empirical work, for instance, saw heavy media discussion that highlighted economic implications of the outbreak in January 2020 (Quandt et al., Citation2020), and by March 2020 public debate over European ‘Coronabonds’ was highly visible (ultimately resulting in the NextGenerationEU agreement in July 2020) (Google trends, Citation2021; European Commission, Citation2021).

What the three-fold arguments for the crises mean for support for EU-level fiscal capacities, we expect, is two-fold. First, we expect that people in regions impacted more heavily by any one of the three crises, or their combination, should more likely expect to be net beneficiaries from and hence support proposals to expand EU fiscal capacities generally, averaging across various design possibilities for such capacities. Given the distinctiveness of the migration crisis, where net beneficiary status might be complicated particularly by cultural-identity considerations, this expectation might be more modest. And the particular urgency and timing of the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic might make the expectation hold more strongly for regional covid exposure. But we expect each regional crisis measure to be associated with stronger support for EU fiscal capacity. We also expect the combination of the crises for a given region – averaging a given region’s exposure to standardised measures of the three crises – to spur support for general EU fiscal capacity, accepting that a region might be unusually hit by one crisis and spared by another. The combined crises might even more strongly spur such support than any single crisis measure, since their cumulation might remind residents of compound and multiple risks, for which a general EU fiscal capacity can provide compensation and insurance. Such reasoning supports a first, general, hypothesis:

H1: Regional crisis exposure and general support for EU fiscal capacity:

Compared to citizens in regions with lower crisis exposure (e.g., lower Covid-19 infection rates, GDP drop since 2008, and/or net migration since 2013), citizens living in regions with higher crisis exposure are more likely to support European fiscal capacity schemes on average.

H2: Regional crisis exposure on type of EU fiscal capacityFootnote3:

Compared to citizens in regions with lower crisis exposure (e.g., lower Covid-19 infection rates, GDP drop after 2008, and/or net migration since 2013), citizens living in regions with higher crisis exposure are more likely to support European fiscal capacity schemes that feature (H2a) no budgetary conditions (vs. budgetary conditions), (H2b) redistribution (irrespective of country wealth vs. no redistribution), (H2c) higher taxation of rich individuals (vs. no taxation), and (H2d) no fines in case of non-compliance with conditions (vs. termination and fines).

Methodology

To investigate the effects of regional crisis exposure on preferences for EU fiscal capacity, we employ public opinion data from a conjoint experiment (Beetsma et al., Citation2022), fielded among 7,490 respondents in five countries (France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Spain), during a unique point in time, namely amid the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic in Europe. In particular, the survey was fielded when the first wave of the Covid-19 crisis reached its first peak in countries such as Italy and Spain and was rapidly unfolding in other countries, together providing an important snapshot of Europeans’ opinions towards transnational fiscal solidarity. Equally important, during this time, there was high variance between regions regarding the local severity of the Covid-19 crisis (in terms of mortality and infection rates). At this early stage of the pandemic in Europe, it is reasonable to assume that the regional spread of the virus and other forms of regional inequality are still largely independent from one another. Furthermore, being a conjoint experiment, this dataset offers a detailed assessment of citizens’ preferences towards European fiscal capacity policies which also addresses the multidimensionality of fiscal integration policy. By merging several regional-level variables to this survey data, we created a dataset with a complex multilevel structure, which demands close analytical attention. H1 is tested by regressing each regional risk factor, the conjoint dimensions, and a set of individual-level control variables on policy support, employing fixed effects to account the data’s multilevel structure. H2 is then tested by adding interaction terms between the regional risk indicator and the conjoint dimensions to the regression analyses employed to test H1. We lay out our research design by first describing the survey dataset, its historical timing, and the general structure of the final dataset. We next describe the main variables of interest, before concluding this section with our analysis strategy.

Data

This study builds on a representativeFootnote4 survey experiment (Beetsma et al., Citation2022), conducted between March 24th, and April 7th, 2020, among 7,490 respondentsFootnote5 from 87 regions in France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Spain. The experiment analyses citizens’ preferences towards different variations of European fiscal capacity instruments to combat adverse temporary or permanent economic shocks hitting member states. Herein, respondents are confronted with several randomly generated policy packages, each varying on a set of crucial policy dimensions, and asked to rate and rank the presented options. This survey experiment included six policy dimensions: budgetary conditions, spending area, role of the European Commission, redistribution, taxation, and fines (see Table 2). Each dimension includes several alternatives (or features), which are randomly combined to form six policy packages, which are presented to respondents in pairs. As each respondent evaluates a total of six packages, the unit of observation is not the individual, but the package, resulting in a total sample of 44,940 evaluations nested within 7,490 individuals. Being exposed to a package pair, respondents are asked to select their preferred policy package (package choice), and to rate each package on a five-point Likert scale (package support). In this study, we focus on the dependent variable package support.

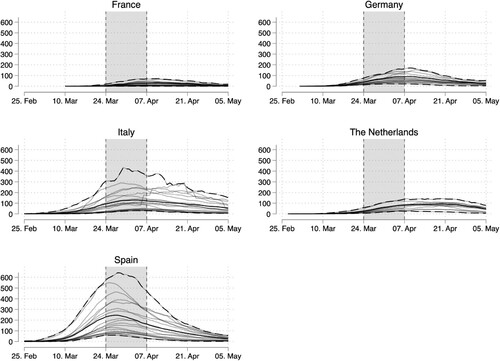

The timing of the survey experiment used in this study must be highlighted. As mentioned above, the survey was conducted between March 24th and April 7th, 2020, therefore amid the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic in Europe. As illustrates, during this time Covid-19 infection rates peaked in Italy and Spain and were on a steady rise in Germany, France, and the Netherlands. Throughout the entire data collection period (indicated by the shaded area in ), Italy, Spain and France were in lockdown, while less-strict shutdown and social distancing policies were in place in Germany and the Netherlands. Note that one should compare the absolute incidence values between countries with caution, as, especially during the first wave of the pandemic, countries varied in their testing strategies and therefore also in their extent of infection rate measurement error.Footnote6 Although all five countries of interest were affected by the Covid-19 pandemic during this early stage of the pandemic, highlights a high amount of variation within countries. This is because, in Europe, the pandemic at first only spread in few epicentres. For instance, while Northern Italy was one of these epicentres throughout the first wave, with Valle d’Aosta reaching a peak 14-day incidence rate of 433.48 on March 30th, infection rates were much lower in the country’s south, with most southern regions having an at least four-times smaller 14-day incidence rate throughout the first wave compared to Valle d’Aosta’s peak.

Figure 1. Daily 14-day case notification rate per 10,000 population by region and country. Note: The grey area indicates the survey data collection period. Daily minimum and maximum incidence values highlighted via dashed lines. The solid non-transparent line indicates the country mean.

To test how regional crisis exposure affects preferences for EU fiscal capacity, we merged several subnational regional-level variables to the survey dataset. All regional-level variables are measured on the NUTS-2 level (except for Germany), matched to the respondents’ region of residence at the time of the survey.Footnote7 Therefore, the resulting final dataset has a multilevel structure, with packages nested in individuals, individuals nested in regions, and regions nested in countries.Footnote8 The final dataset therefore contains 44,940 observations from 7,490 respondents nested in 87 regions across 5 countries.

Variables

We test our hypotheses using the dependent variable package support. In the survey experiment, this variable is assessed for each package, after presenting a package pair, on a 5-point scale ranging from ‘strongly against’ to ‘strongly in favour’. To compute overall levels of support, it is crucial to know what percentage of the population likes or dislikes a certain package. We therefore transform this ordinal variable into a dichotomous one, by recoding strongly opposed, opposed and neutral observations as 0, and favourable and strongly favourable observations as 1 (Mean = .40, SD = .49). This conservative measure of support has also been employed by other subgroup analyses of conjoint experimental data (e.g., Hainmueller & Hopkins, Citation2015; Kuhn et al., Citation2020).

Our central independent variables are various indicators of subnational socio-tropic context. All regional-level variables are measured on the NUTS-2 level except in Germany, where we opt for the NUTS-1 level instead.Footnote9 provides descriptive statistics of the main regional variables of interest, by country and for the total sample.Footnote10

Table 1. Descriptive statistics by country.

We measure the regional-level impact of the Covid-19 pandemic through the weekly excess mortality rate, which indicates the extent to which the regional number of deaths in a particular week exceeds the mean number of deaths in the same week in previous years. Regional excess mortality is calculated by subtracting the weekly mean mortality (in percentage points) in 2015–2019 from the corresponding week’s mortality (in percentage points). The resulting variable therefore indicates by how many percentage points the regional mortality has increased in a week in 2020 compared to the same week in 2015–2019. The value 0 indicates no change, whereas the values −1 and 1 indicate a comparative decrease and increase by one percentage point, respectively. As especially throughout the first wave most excess deaths are accredited to Covid-19 infections, excess mortality is a commonly used indicator of the regional impact of the pandemic (e.g., Annaka, Citation2022; Díaz Ramírez et al., Citation2022; Zaki et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, like infection rates, the number of Covid-19-related deaths is a statistic often used in the media and public debate to highlight the regional severity of the pandemic, especially throughout its first wave. However, unlike infection rates (see Wagner et al., Citation2021), the excess mortality statistic is less prone to measurement errors/biases, and therefore more comparable across countries. Appendix 1, Figure A1 shows a map of the excess mortality in the surveyed regions in week 13, 2020 (start of the survey period). The to-be-expected pattern emerges, where certain regions, such as northern Italy or Madrid, Paris and their surroundings, were more heavily affected by the pandemic in terms of excess mortality throughout its first wave.

Equally important to our conception of crisis in contexts, we estimate the regional-level impact of two past crises, namely the 2008 financial crisis and the refugee crisis 2015. To receive an estimate of the medium- and long-term effect of the financial crisis on subnational European regions, we calculate the mean yearly GDP per capita between 2008 and 2019 minus the mean yearly GDP per capita between 2000 and 2007 – with less positive or more negative values indicating a GDP increase in time, and more positive or less negative values indicating a relative decrease. This gives us an approximation, where larger values indicate a higher, more painful regional-level impact of the financial crisis. We refer to this variable as GDP drop. Appendix 1, Figure A2 illustrates the regional distribution of GDP drop in the five countries. The largest variation in GDP drop seems to be concentrated between countries, with Germany and the Netherlands having experienced a smaller drop in GDP since 2008 as compared to Italy, France and Spain. Regardless of the country-level differences, there are also clearly visible regional-level differences in GDP drop, for instance showing a North–South divide in Italy and Spain as well as a lower GDP drop in former Western Germany as compared to former Eastern German counties.

To estimate the regional impact of the refugee crisis, we adapt a similar approach as Georgiadou et al. (Citation2018) and Nicoli and Reinl (Citation2020), and look at regional-level changes in migration. We employ migration data instead of data on asylum applications as the latter is only available at the national level. In contrast to Georgiadou et al. (Citation2018) and Nicoli and Reinl (Citation2020), however, we employ the yearly statistics on regional net migration rates, therefore also taking emigration into account besides immigration, to account for refugees moving further to another country. To estimate the regional uptake of asylum-seekers, we calculate the difference in mean yearly net migration rate (per 1000 inhabitants) between 2013 and 2016 from the mean yearly net migration rate between 2010 and 2012. This variable, which has higher values for regions which saw an increased net migration from 2013 onwards, gives us an approximation of how much the intake of refugees has increased in a region during the migration wave between 2013 and 2016, while accounting for regional emigration and population sizes. We generally refer to this variable as migration change or migration difference. It seems that most variation is concentrated on the country-level, with Germany displaying the strongest increase in net migration, which aligns with Germany accepting the highest number of asylum applications in 2015. Still, a non-negligible amount of variation is visible on the NUTS-2 regional level, for instance with higher levels of net migration change in more southern regions in Italy.Footnote11

Lastly, we construct a composite measure by standardising and averaging the three aforementioned regional crisis-related risk factors. The crisis indicators excess mortality, GDP drop and migration change are only weakly correlated with an average interitem covariance of 0.19. While the correlation between excess mortality and GDP drop is the lowest (r = 0.02), migration change negatively correlates with excess mortality (r = −0.26) and GDP drop (r = −0.28). The regional distribution of the crisis composite measure depicted in Appendix 1, Figure A4 reflects this lack of a clear pattern across the three selected crises.

Testing our second hypothesis requires another set of independent variables, namely the treatments of the conjoint experiment, which are the randomly assigned values for each of the six package dimensions. For each observation, there is a set of six independent experimental treatments, each indicating the type of condition, spending area, role of the European Commission, redistribution, taxation, and fines the observed hypothetical policy package involves. The randomisation of each package dimension’s feature (or treatment) ensures that the estimated differences due to the treatments can be interpreted as causal. An overview of the dimensions and their corresponding features is provided in . As we only hypothesised moderations of the treatment effects through socio-tropic contexts for four of the six policy dimensions (condition, redistribution, taxation, and fines), we also only focus on these four dimensions throughout our analysis. The first dimension of interest, budgetary conditions, has two possible values and focuses on whether the policy features any conditions that must be fulfilled to get support (reference category: no conditions). The second dimension of interest, redistribution, has three possible features and states whether countries can receive more from the programme than they pay into it. According to this dimension, packages either feature no redistribution (reference category), potential redistributive effects for all countries, or redistribution only to poorer countries.Footnote12 The third dimension of interest is taxation and asks whether the policy programme will affect taxes in the respondent’s country. Its features are no impact (reference category), a 0.5% tax increase for everyone, or a 1% tax increase for rich individuals.Footnote13 Lastly, the fourth dimension of interest, fines, focuses on whether budgetary support shall be terminated and countries should pay an additional fine should they violate the conditions of the support programme (reference category: no automatic termination).

Table 2. Conjoint experiment – wording of the conjoint dimensions.Footnote17

Furthermore, to control for regional composition effects, we include various individual-level variables in our regression models, namely gender, age, education, income, and unemployment experience. Gender is coded 0 for male respondents and 1 for female respondents.Footnote14 Age is estimated by subtracting respondents’ year of birth from the survey year, while education and income are coded as ordinal variables (levels: low, medium, high) and employment status is coded 0 for respondents who have not and 1 for respondents who have been unemployed for more than three months in the last 5 years.

Analytical strategy

We analyse how regional crisis exposure affects preferences for EU fiscal capacity measures employing various multilevel linear regression models explaining the dependent variable package support through all six package dimensions, all aforementioned individual-level variables and each respective regional risk factor, while taking the multilevel structure into account by employing fixed country, dateFootnote15, region, and individual effects. To avoid multicollinearity, we run a separate model for each regional risk factor. These baseline models are employed to estimate the effects of the regional risk factors on general support for European fiscal integration policies, regardless of the policy design details (H1). To test our second hypothesis, we extend the baseline model by adding interaction terms of the regional risk factor with each of the six package dimensions. This approach is in our case a more valid test of our hypothesis than the split-sample approach suggested by Leeper et al. (Citation2020), as splitting the moderating variables into subgroups (using an arbitrary cut-off point) disregards potentially important variance of moderating variables, which is not lost when employing interaction models. Furthermore, the interaction-model approach allows us to fully take account of the multilevel structure of the dataset. Based on these regression models, we furthermore plot estimated marginal means of all interaction effects hypothesised in H2.

Results

General effects of socio-tropic contexts on policy support

H1 states that general support for European fiscal integration varies across different socio-tropic contexts, measured as regional exposure to Covid-19 infection rates, GDP drop post-2008, and/or increased net migration rates post-2013. We test this hypothesis for three different crisis-related regional risk factors, namely the regional Covid-19 excess mortality rate, the regional drop in GDP as compared to pre-2008-crisis levels, and the difference in net migration from 2013 to 2016 as compared to migration levels prior to the increased influx of asylum seekers. The full results of the multilevel linear fixed effects regression models on the dependent variable package support through the conjoint dimensions, individual-level control variables and each regional risk indicator are presented in Appendix 2. Regarding the effect of the regional covid impact on general support for EU fiscal capacity policies, we find that an increased regional excess mortality in the week of survey response date is associated with an increased general support for the presented fiscal capacity policies, B = .0060, SEB = .0030, β = .0062, SEβ = .0031, p = .042. Based on this estimation, a 1-percentage-point-increase in regional excess mortality is associated with a 0.60-percentage-point-increased predicted probability to support EU fiscal budget instruments in general. However, this result is not robust to employing our alternative measure of the covid crisis impact, 14-day incidence rates. For the other singular regional risks (GDP and net migration change), no significant relation with policy support is observable, indicating that regional crisis impact of the refugee crisis or the economic crisis alone did not affect general support for EU fiscal capacity. We do find a significant positive relation between policy support in general and our regional crisis composite measure, β = .0176, SEβ = .0078, p = .024, which is the regional mean of all standardised crisis indicators. This relationship is largely driven by the effect of regional excess mortality on general policy support, as a robustness check removing excess mortality from our composite measure yielded no significant relation. Nonetheless, the composite measure explains 2.8 times more variation in the dependent variable package support than excess mortality, which supports our expectation of a cumulative crisis effect.

Interactions of socio-tropic contexts with policy dimensions

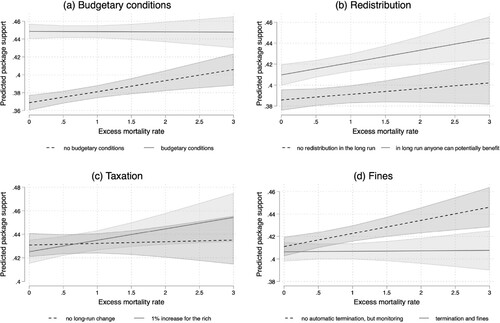

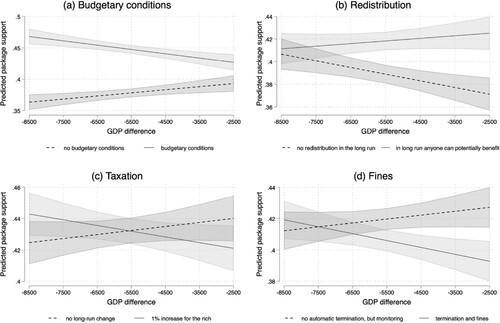

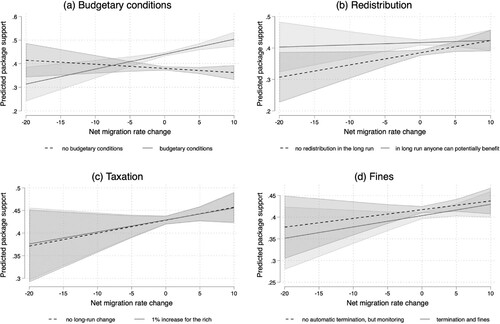

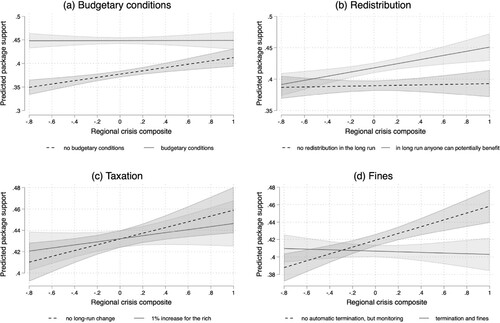

To test whether socio-tropic contexts affect citizens’ preferences for certain variants of EU fiscal capacity policies, we ran another set of regression analyses in which we additionally interact the regional risk factor with all conjoint dimensions. displays the interaction coefficients derived from the three regression analyses testing H2 (full table in Appendix 3). All regression models are linear multilevel models explaining package support and take variations on the country level, regional level, date level and individual level into account using fixed effects and controlling for the individual-level variables gender, age, education, income, and employment status. Each model tests H2 for a different crisis-related regional variable. Model 1 predicts interactions between excess mortality and the conjoint dimensions, Model 2 tests the interactions of the crisis-related regional GDP drop with the conjoint dimensions, Model 3 estimates the interactions of the regional migration change related to the influx of asylum-seekers in 2013–2016 with the conjoint dimensions, and Model 4 projects the interactions of the conjoint dimensions with the regional crisis composite measure. To improve the interpretability of the interaction effects, relevant marginal means, as predicted by the interaction models through the four selected package dimensions and moderating variables, are plotted in .

Figure 2. Marginal means of package support by conjoint dimensions and excess mortality rate, with 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 3. Marginal means of package support by conjoint dimensions and regional GDP drop (2008–2019 vs. 2000–2007), with 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 4. Marginal means of package support by conjoint dimensions and regional net migration rate change (2013–2016 vs. 2010–2012), with 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 5. Marginal means of package support by conjoint dimensions and regional composite measure, with 95% confidence intervals.

Table 3. Standardised interaction coefficients from the linear multilevel regressions explaining package support.

The results in this section are robust to several alternative model specifications. Neither the choice of regional covid impact indicator (alternative: 14-day incidence rate; see Appendix 3), nor the choice of regional economic crisis impact indicator (alternative: change in employment rate after 2008; see Appendix 3), nor splitting the sample by individual-level income (low, medium, high; see Appendix 4) led to a substantial change of the results.

The results from the regression analysis shown in , Model 1, as well as , suggest a significant moderation of the budgetary conditions dimension through regional excess mortality. As can be seen in (a), a decrease in regional excess mortality leads to more pronounced effects on the budgetary conditions dimension. While the generally higher support for packages that feature budgetary conditions remains constant, independently of regional mortality, the probability to support packages featuring budgetary conditions significantly increases by 1.2 percentage points when a region’s excess mortality rate increases by 1. Looking at (b), which plots the marginal means of package support by excess mortality for the redistribution dimension, support is significantly higher for packages that feature redistribution to any country, compared to packages that are designed to prevent redistributive effects, but this is not moderated by regional excess mortality. Turning to the effects of regional excess mortality on the taxation feature effects ((c)), a higher regional excess mortality does not affect support for packages that feature no change in taxation, while it increases support for packages that feature a 1% percent tax increase for the rich. Lastly, (d) indicates that the effects of the ‘termination and fines’ features are significantly moderated by regional excess mortality. Looking at respondents in regions with an excess mortality rate below 0.8, support for policy packages that feature termination and fines does not differ from packages that do not feature termination and fines. However, as support for packages featuring no termination and fines slightly increases and support for packages featuring termination and fines slightly decreases as excess mortality values increase, we can observe that, only in regions with an excess mortality rate of more than 0.8, respondents are significantly more supportive of packages that only intend monitoring in case of non-compliance than of packages that implement automatic termination and fines.

Overall, these results are robust to our alternative approach to measuring the regional-level pandemic impact, namely through 14-day incidence rates (see Appendix 4). Furthermore, to address concerns that the initial regional covid impact was similarly geographically distributed as the regional hardship experienced throughout and beyond the 2008 financial crisis (e.g., higher levels of both crises’ impact in Spain and Italy), we also run regressions additionally controlling for interactions between the conjoint dimensions and GDP-drop and the interactions between the conjoint dimensions and migration change.Footnote16 Although these models lack statistical power and should be interpreted with caution, the results regarding excess mortality remain robust. This is not surprising considering the low correlation between these two regional crisis indicators (r = 0.02).

Turning to the moderating effects of regional GDP drop, we can observe similar effects as previously observed for regional Covid-19 incidence rates. Like an increase in Covid-19 incidence, a stronger regional GDP drop (indicated through less negative values on the scale) compared to pre-2008 levels is associated with weaker support for packages that feature budgetary conditions and higher support for packages that do not ((a)). Generally, support for budgetary conditions is larger than support for no budgetary conditions. However, the difference in levels of support becomes smaller with an increasing GDP drop since the crisis dawn in 2008. Compared to regions with a €2000 lower GDP drop after 2008, less prosperous regions were 1.0 percentage points more likely to support packages without budgetary conditions and 1.4 percentage points less likely to support packages with budgetary conditions. Furthermore, looking at the redistribution dimension, the effect of redistribution features on policy support is also moderated by regional GDP drop. As (b) shows, in most regions, support for packages allowing redistribution to any country is higher than support for packages restricting redistribution effects. However, in regions that experienced a drop in yearly mean GDP levels of −6900€ or less since 2008, no significantly different levels of support are visible for the redistribution dimensions. Again, we find no significant interaction effects between GDP drop and the taxation dimension ((c)). Lastly, the regression results indicate a significant moderation of the effect of the fines dimension through regional GDP drop ((d)). In regions with a GDP drop of −€5,500 or more, packages that do not feature termination and fines in case of non-compliance are significantly more likely to be supported than packages that do feature termination and fines. In regions that experienced a lower drop in GDP than −€5,500 since 2008, the differences in support levels between the two features become non-significant. These results are largely robust to employing an alternative measure of the regional impact of the economic crisis, namely the change in regional employment rates after 2008 (see Appendix 4). In sum, the results from these interactions largely support the claims postulated in H2.

Turning to , which depicts the results testing H2 for the variance in changes in regional net migration, we can observe a significant moderation effect with the budgetary conditions dimension of the conjoint experiment ((a)). While the effect of the ‘no budgetary conditions’ feature remains statistically constant across regions, support for packages featuring budgetary conditions significantly increases if an individual’s region had a higher level of net migration in 2013–2016 compared to previous years. In regions with a net migration rate change of −3 or higher, respondents are significantly more likely to support packages that feature budgetary conditions than to support packages that refrain from budgetary conditions. For the remaining three dimensions of interest, we find no significant moderations with regional migration change. Therefore, H2 only finds partial support with regards to the migration shock.

Finally, shows the (similar) moderating results of focusing on our composite measure of regional crisis exposure that combines the three crises (standardised excess mortality, net migration rate change, and GDP drop). For the budgetary conditions dimension ((a)), we find that support for an EU fiscal capacity without budgetary conditions significantly increases as cumulative regional crisis impact increases, while support for budgetary conditions remains stable. Turning to the redistribution dimension ((b)), we find that redistributive packages find significantly higher support in more crisis-ridden regions, while support for non-redistributive packages remains constant. While we find no significant moderations of the taxation dimension ((c)), we do find that policy packages that do not enforce termination and fines find more support in regions scoring higher on the regional crisis composite measure, while no significant differences emerge for moderations with the automatic termination and fines attribute ((d)). Overall, respondents in regions hit harder by the accumulation of crises were found to be more supportive of more redistributive and less restrictive packages, again with exception of the taxation dimension.

Importantly, the effects of the composite measure go beyond the simple summation of the individual crisis effects. As a comparison of the standardised regression coefficients in shows, the effect sizes of our composite measure interacted with each of the conditions, redistribution and fines dimensions always exceed the effects of each individual crisis indicators’ respective interaction as well as the summation of the individual crisis indicators’ respective interaction effects. This provides further evidence for our expectation that accumulated regional-crisis pain spurs support for more permissive and redistributive fiscal capacity designs more than do the single regional-crisis measures.

Conclusions

Focused upon how regional exposure to multiple crises can be important to EU politicisation, this study has investigated how regional contexts (regional covid-related excess mortality, pre- vs post-2008 GDP decline, and pre- vs post-2013 net migration rates) moderate citizens’ preferences for different variants of European fiscal policies. Our study has done so while also controlling for individual-level risk correlates and country-level fixed effects. Our key findings are two-fold. First, we find that subnational differences in exposure to crises only increase general support for EU fiscal capacity for the most recent crisis (covid) and in composition, while the remaining singular 2015 refugee- and 2008 economic crises do not significantly spur such support in general. The positive relation with the regional crisis composite is likely driven by the effect of regional excess mortality, as our robustness check excluding excess mortality from the composite yields no significant relationship. For the migration and economic crisis, citizens seem to differentiate between different versions of fiscal capacity instruments, with higher levels of support for some packages and lower support for others, therefore averaging out across the many possible designs. Our interpretation is that only particularly salient regional-level crises are likely to significantly shape support for European fiscal capacity in general. Second, we find that regional crisis exposure does play a not-to-be-neglected role in spurring support for more permissive and redistributive EU fiscal capacity – that is, EU fiscal capacity that is less rather than more conditional upon budget balancing, more rather than less redistributive in allowing net transfers between countries and between individual tax payers, and less punitive with respect to non-compliance. These patterns are weaker with respect to net migration rates, in line with findings with our theoretical expectation that migration sparks budgetary caution (Hanson et al., Citation2007) that can diminish embrace of more EU fiscal capacity that does not explicitly address such caution. Nonetheless, the basic pattern of regionally crisis-ridden people supporting permissive and redistributive EU capacities holds for our measure combining the multiple crisis measures. And again, these regional-level crisis results obtain net of country-level fixed effects and individual-level correlates of risk and economic struggle.

In sum, regions harder hit by crises appear to be more supportive of more permissive European fiscal integration policies. Considering polycrisis in a way that takes account regional context shows relevant (new) forces for positive politicisation of EU capacities and integration. People do not only form their political opinions based on individual self-interest but are also aware of their subnational regional (and possibly socio-tropic) context. The observed effect sizes are relatively small, indicating that regional-level crisis experience does not seem to be the driving force behind support for different variants of EU fiscal policy. But regional crisis context has the potential to become decisive over public majorities in favour of such policies.

We offer these findings mindful of the study’s limitations and of the importance of further research into the role of socio-tropic contexts on support for EU capacities. First, our measures of region-based crisis should be further expanded. For instance, our measure of regional covid impact, excess mortality rate (or 14-day incidence rates), and of the migration crisis impact, change in net migration, are not the only or even ideal indicators of regional crises’ economic impact. Ideally, one could combine such measures with other factors with a more direct economic impact, such as regional-level lockdown measures. However, such data are only available on the national level (e.g., Hale et al., Citation2021).

Second, although the effects of the policy dimensions can be interpreted as causal, the moderations of these effects through regional context are observational. This is of less concern when interpreting effects of regional crisis (such as infection rates, due to their exogenous character). But a slightly different picture emerges when looking at regional net migration and wealth loss, where regional wealth loss since 2008 and opinions about policy dimensions may also be a product of shared collective values or other unmeasured conditions. Theoretically, however, the view that regional wealth influences policy preferences, instead of reflecting values or other confounders, seems more likely given the stability of the results across models and panels of controls.

Third, our measure of the regional refugee-crisis impact, focusing on recorded net migration differences, might understate the impact of refugee arrival and other passthrough regions. In these regions, not all migrants stay and may thus not be counted as part of the measurement, despite costs imposed on these regions. Alongside other previously discussed explanations, this might help account for migration crisis’ weaker effects on support for more generous EU fiscal support.

Last, but certainly not least, the timing of the survey experiment, which benefitted the internal validity of this paper, has implications for the external validity of the results over time. We have already discussed that this colours any comparisons we make between the Covid-19 crisis and other two crisis-measures (GDP loss since 2008 and net migration since 2013). The high salience for the Covid-19 crisis means our inferences should be further tested in more neutral times with respect to crisis experience. The timing of the survey also calls for caution with respect to the measures. As Italy and Spain were most affected by the pandemic at the time of the survey, the moderating effects of regional excess mortality rates on support for various packages may be particularly driven by the Italian and Spanish patterns. Also, at the early stage of the pandemic, insecurity was particularly high due to the unfamiliarity with the situation, which might have overshadowed the effect of typical heuristics (e.g., Kyriazi et al., Citation2023). All such issues deserve further exploration.

In the meantime, our results do provide significant traction for seeing that regional-level crises studied in combination, even at a given point in time, can shed light on the most basic dynamics of polycrisis in EU politicisation. Multiple but very distinct crises can matter at the regional, and not just individual or country levels, and a region’s exposure to their combination can meaningfully shape support for (more permissive) EU fiscal capacities.

Competing interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (3.8 MB)Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this paper have been presented at the Amsterdam special issue workshop, the Cologne Center for Comparative Politics Research Seminar, and the ECPR General Conference 2022. We thank the anonymous reviewers for JEPP, Francesco Nicoli, Jonathan Zeitlin, Theresa Kuhn, Sven-Oliver Proksch, Alexia Katsanidou, Jens Wäckerle, Paula Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik, David van der Duin, Christian Freudlsperger, Jasmin Rath, Anne-Kathrin Stroppe, Hauke Licht, Emma Kessenich, and Manuel Wagner for valuable comments. We are grateful to Roel Beetsma, Francesco Nicoli, Anniek de Ruijter, and Frank Vandenbroucke for access to the survey dataset.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lukas Hetzer

Lukas Hetzer is a Doctoral Researcher at the University of Cologne, Cologne Center for Comparative Politics.

Brian Burgoon

Brian Burgoon is Professor of Political Economy at the University of Amsterdam, Department of Political Science.

Notes

1 Abbreviation for “Nomenclature of Territorial Units of Statistics”, is the geocode standard developed by the EU to capture intra-national territorial regions. We employ the NUTS-2 level for all countries except for Germany, where the NUTS-1 level is used.

2 Permissiveness may also entail less conditionality on how fiscal assistance is spent or less monitoring by EU authorities. We consider (and find support for) these possibilities as well, but we put our emphasis on the conditions most obviously related to permissive and generous EU fiscal capacity.

3 See footnote 2.

4 The survey is representative of each country’s population in terms of education, age, gender, and regional distribution (Beetsma et al., Citation2022, p. 9).

5 In contrast to the project’s main paper (Beetsma et al., Citation2022), this study excludes all respondents that failed the attention check, as well as respondents from the Spanish autonomous cities Ceuta and Melilla, therefore reducing the number of respondents from 10,000 to 8,570. The number of respondents if further reduced to 7,490 due to missing values in the individual-level control variables.

6 For this reason, we do not mainly analyse the regional impact of the Covid-19 pandemic through infection rates, but through excess mortality rates (see variables section).

7 This introduces measurement noise for respondents that may have moved NUTS-region in the previous few years, since we explore crisis conditions in previous years (for the financial- and migration-crises). We do expect, however, that questions and judgments expressed at the time of the survey still involve and reflect a resident’s current region and not just or mainly previous residence(s).

8 Strictly speaking, each package is also nested in a package pair. However, as we employ the package support variable and not the package choice variable, the direct comparison between the packages displayed as pairs becomes less relevant, and this level may therefore be ignored in the statistical analysis.

9 In most countries, the NUTS-2 level is politically and culturally meaningful for historical reasons. In Germany however, the Bundesländer, measured on the NUTS-1 level have a historically more relevant status than the Landkreise, measured on the NUTS-2 level. Furthermore, as the survey dataset combines the Italian NUTS-2 regions of Bolzano (ITH1) and Trento (ITH2), we combine the values of all regional level variables for these regions as well, by calculating their population-size-adjusted mean.

10 A more detailed presentation of the regional distribution of the crisis risk factors is provided by the maps in Appendix 1.

11 See Appendix 1, Figure A3 for the geographic distribution of migration change.

12 As our hypotheses focus on the effect of redistribution to all countries (vs. no redistribution), we disregard the policy feature redistribution from rich to poor in the analysis.

13 As hypothesized, we only focus on the impact of taxation of the rich (vs. no change in taxation), and therefore disregard the policy feature 0.5% tax increase for everyone in the analysis.

14 Two respondents identified as ‘other’ than male or female. These had to be excluded from the analysis, as they did not respond to other relevant items such as income or employment status.

15 As the data collection period was highly eventful, we can expect respondents’ preferences for EU fiscal capacities to change daily. For instance, the discussion about European Coronabonds gained new traction and reached a new peak towards the end of March, halfway through the data collection phase (Google Trends, Citation2021). Therefore, we also account for the factor of time in our models through day-level fixed effects.

16 See Appendix 6.

17 The dimensions spending areas and EC’s role are also part of the conjoint experiment but not listed in this table, as they are not the primary focus of this study’s priors. Furthermore, the features redistribution from rich to poor and 0.5% tax increase for everyone, as part of the Redistribution and Taxation dimensions, respectively, are not the focus of our analysis and therefore also excluded from the table.

References

- Alessi, L., Benczur, P., Campolongo, F., Cariboni, J., Manca, A. R., Menyhert, B., & Pagano, A. (2020). The resilience of EU member states to the financial and economic crisis. Social Indicators Research, 148, 569–598.

- Almeida, V., Barrios, S., Christl, M., De Poli, S., Tumino, A., & van der Wielen, W. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on households' income in the EU. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 19(3), 413–431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-021-09485-8

- Amdaoud, M., Arcuri, G., & Levratto, N. (2021). Are regions equal in adversity? A spatial analysis of spread and dynamics of COVID-19 in Europe. The European Journal of Health Economics, 22(4), 629–642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-021-01280-6

- Anderson, C. J., & Reichert, M. S. (1995). Economic benefits and support for membership in the E.U.: A cross-national analysis. Journal of Public Policy, 15(3), 231–249. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00010035

- Androutsou, L., Latsou, D., & Geitona, M. (2021). Health systems’ challenges and responses for recovery in the pre and post COVID-19 era. Journal of Service Science and Management, 14((04|4)), 444–460. https://doi.org/10.4236/jssm.2021.144028

- Annaka, S. (2022). Good democratic governance can combat COVID-19 – Excess mortality analysis. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 83, 103437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103437

- Basile, R., Mantuano, M., Girardi, A., & Russo, G. (2019). Interregional migration of human capital and unemployment dynamics: Evidence from Italian provinces. German Economic Review, 20(4), e385–e414. https://doi.org/10.1111/geer.12172

- Beetsma, R., Burgoon, B., Nicoli, F., De Ruijter, A., & Vandenbroucke, F. (2022). What kind of EU fiscal capacity? Evidence from a randomized survey experiment in five European countries in times of corona. Economic Policy, 37(111), 411–459. https://doi.org/10.1093/epolic/eiac007

- Bobzien, L., & Kalleitner, F. (2021). Attitudes towards European financial solidarity during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from a net-contributor country. European Societies, 23(sup1), S791–S804. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2020.1836669

- Boeri, T. (2010). Immigration to the land of redistribution. Economica, 77(308), 651–687. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0335.2010.00859.x

- Boin, A., Ekengren, M., & Rhinard, M. (2020). Hiding in plain sight: Conceptualizing the creeping crisis. Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy, 11(2), 116–138. https://doi.org/10.1002/rhc3.12193

- Bremer, B., Kuhn, T., Meijers, M. J., & Nicoli, F. (2023). In this together? Support for European fiscal integration in the COVID-19 crisis. Journal of European Public Policy, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2220357

- Burgoon, B., Kuhn, T., Nicoli, F., & Vandenbroucke, F. (2022). Unemployment risk-sharing in the EU: How policy design influences citizen support for European unemployment policy. European Union Politics, 23(2), 282–308.

- Carrubba, C. J. (1997). Net financial transfers in the European union: Who gets what and why? The Journal of Politics, 59(2), 469–496. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381600053536

- Chalmers, A. W., & Dellmuth, L. M. (2015). Fiscal redistribution and public support for European integration. European Union Politics, 16(3), 386–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116515581201

- Colantone, I., & Stanig, P. (2018). Global competition and Brexit. American Political Science Review, 112(2), 201–218. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055417000685

- Colantone, I., & Stanig, P. (2018). The trade origins of economic nationalism: Import competition and voting behavior in Western Europe. American Journal of Political Science, 62(4), 936–953. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12358

- Czaika, M., & Di Lillo, A. (2018). The geography of anti-immigrant attitudes across Europe, 2002–2014. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(15), 2453–2479. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1427564