ABSTRACT

The autocratization of Hungary and Poland prompted a revolution in the European Court of Justice (ECJ)'s caselaw. Brick by brick, the ECJ imposed novel obligations on EU member states to safeguard the rule of law while expanding the legal bases for the EU to sanction governments breaching the Union's fundamental values. In this article, we ask whether the ECJ pioneered this rule of law revolution or, conversely, whether the Court responded to an entrepreneurial European Commission acting as ‘guardian of the Treaties’. While supranationalist theories depict the Commission as a proactive agenda-setter guiding the Court's innovations, studies of the EU's rule of law crisis argue that the Commission dragged its feet or only recently seized the reins of leadership. Which perspective is closer to the mark? Deploying a new theoretical framework to study judicial innovation and agenda-setting on an original dataset of all rule of law cases adjudicated by the ECJ from 2010 through 2023, we demonstrate that the Commission has been an inconsistent and often indifferent agenda-setter. Besides several proactive interventions limited to the latter years of the Juncker Commission, the Court's innovative rulings prompted the Commission to act more than the reverse, belying a fundamental shift in leadership.

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, a revolution has rocked the European Union (EU) and constitutionalised the rule of law (ROL) within its legal order. Prompted by the democratic breakdowns of Hungary since 2010 and Poland after 2015 (Magyar, Citation2016; Sadurski, Citation2019), the EU faced ‘a “constitutional moment”: the decision whether it comprises illiberal democracies or whether it fights them’ (Von Bogdandy et al., Citation2018, p. 984). As member governments and the European Council dragged their feet for several years (Kelemen, Citation2023; Pech & Scheppele, Citation2017), the European Court of Justice (ECJ) asserted itself and constitutionalised novel obligations for member states to safeguard the ROL. From requiring states to maintain independent judiciaries to transforming the EU's democratic and ROL values into binding commitments whose violation legitimates the suspension of EU funds, the Court has been hard at work crafting innovative judgments (Ovádek, Citation2023; Pech & Kochenov, Citation2021; Spieker, Citation2023).

This is not the first time that the ECJ has spearheaded a legal revolution. In the 1960s, French President Charles de Gaulle – whose attacks on judges presaged the tactics of Hungary's Viktor Orban and Poland's Jaroslaw Kaczynski (Möschel, Citation2019) – paralysed the Council of Ministers in the ‘empty chair crisis’ (Palayret, Citation2006). It was during the ensuing ‘doldrum years’ of ‘eurosclerosis’ (Caporaso & Keeler, Citation1995; Giersch, Citation1985, p. 37) that the ECJ ‘stepped in to hold the construct together’ (Weiler, Citation1991, p. 2425). The Court developed its innovative doctrines of the primacy and direct effect of EU law, mutual recognition, and fundamental rights to advance integration and proclaim Europe as a community based on the ROL (Alter & Meunier-Aitsahalia, Citation1994; Mancini & Keeling, Citation1994; Vauchez, Citation2010).

Yet the ECJ was not alone in past quests to reshape EU law. The European Commission proved an eager ally and agenda-setter, inviting the Court to make many of its innovative rulings in the 1960s and 1970s (Rasmussen, Citation2014) and wielding ECJ judgments to propose new policies (Alter & Meunier-Aitsahalia, Citation1994). It is precisely this co-authored ‘integration through law’ agenda that was jeopardised once Hungary and Poland autocratized (Baquero Cruz, Citation2018; Kelemen, Citation2019). These developments raise a crucial question: have the ECJ's innovative judgments been prompted by an entrepreneurial Commission as in years past, or has the ECJ seized the mantle of leadership to pioneer a ROL revolution?

This query lies at the heart of debates concerning judicial policymaking and agenda-setting in the EU. In classic supranationalist theories, ‘the Commission and the Court routinely generat[e] important policy outcomes’, with most of these accounts stressing the Commission as the ‘vanguard’ with a first-mover advantage (Stone Sweet, Citation2010, p. 20; Pollack, Citation1998, p. 217; Stone Sweet & Brunell, Citation2012). Even studies questioning the Commission's influence as a legislative agenda-setter seldom dispute its influence as a judicial agenda-setter (Becker et al., Citation2016; Deters & Falkner, Citation2021; Hodson, Citation2013; Nugent & Rhinard, Citation2016). As it launches infringements against member states (under Articles 258 and 260 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU)) and intervenes in cases referred to the ECJ by national judges (Article 267 TFEU),Footnote1 the Commission wins 90% of the lawsuits it brings (Stone Sweet & Brunell, Citation2012, p. 208; Kelemen & Pavone, Citation2023, p. 14) and wields its ‘repeat player’ advantage to shape the Court's agenda (Hofmann, Citation2013; Snyder, Citation1993). Applying this perspective to the ROL field, Hooghe and Marks (Citation2019, pp. 1125–1126) highlight ROL-related infringements lodged by the Commission as evidence of its ‘supranational activism’, and Pircher (Citation2023, pp. 774–775) casts the Commission as an ‘engine for continued integration’ precisely because it brings ‘the most severe cases of non-compliance (e.g., rule of law)’ to the ECJ.

Conversely, most studies of the EU's ROL crisis argue that the Commission has dragged its feet, exposing the Court as ‘the last soldier standing’ (Kochenov & Bard, Citation2020). Consistent with arguments that a ‘constraining dissensus’ and ‘new intergovernmentalism’ restrain Commission entrepreneurship in contentious policy fields (Bickerton et al., Citation2015; Hooghe & Marks, Citation2009), these scholars posit that the ‘guardian of the Treaties’ has consistently been reluctant to pursue ROL cases due to intergovernmental resistance (Closa, Citation2019; Kelemen, Citation2023; Kelemen & Pavone, Citation2023; Pech & Scheppele, Citation2017; Soyaltin-Colella, Citation2022). In this view, the Commission has either been missing in action (leaving ‘the Treaties without a Guardian’; see Scheppele, Citation2023, see) or has even obstructed ‘an expansion of the EU's rule of law competences’ (Ovádek, Citation2023, p. 1130). Still more recent studies suggest a ‘fundamental change beneath the surface’, with the Commission pivoting from a reluctant to an assertive stance as a ROL agenda-setter due to a positive shift in intergovernmental support (Blauberger & Sedelmeier, Citation2024; Hernández & Closa, Citation2023; Priebus & Anders, Citation2023). Which of these alternative accounts is closer to the mark?

To answer, we propose a new theory and measurement strategy to study judicial innovations and deploy it on an original dataset of all ECJ decisions and Commission observations in ROL cases: the ECJ-ROL Dataset. The dataset is the most comprehensive repository of the Court's ROL decisions and the only dataset that parses ECJ cases into timestamped events linked to the Commission's observations and extra-judicial writings, enabling researchers to identify the locus of innovations. We analyse these data from 2010 to 2023 – spanning 96 cases, 180 ECJ decisions, and over 15,000 citation points – leveraging a novel framework of judicial innovation and Commission agenda-setting. We theorise that the ECJ renders an innovative ROL decision when it (i) establishes a new legal basis for ROL enforcement, (ii) introduces a new legal principle guiding ROL enforcement, or (iii) makes a judicial innovation ‘bite’ by sanctioning a state for infringing a new ROL legal basis or principle. Leveraging this framework, we map the teleological development of the Court's ROL innovations and identify patterns that may be tied to Commission agenda-setting. We theorise that the Commission can spur judicial innovations directly – via proposals filed before the Court – and indirectly – via extra-judicial writings cited by ECJ judges.

Our analysis contradicts supranationalist accounts of the Commission as a proactive judicial agenda-setter and demonstrates that these arguments do not generalise to the ROL field. Instead of the vanguard driving the Court's ROL revolution, the Commission has served as an intermittent, inconsistent, and often indifferent agenda-setter. The Court repeatedly had to spur the Commission to act through innovative rulings, and there is no evidence that the Commission inspired judicial innovations via indirect agenda-setting. Nonetheless, the Commission has neither ubiquitously dragged its feet nor fundamentally shifted from a reluctant to an assertive stance. Most of the Commission's acts of proactive agenda-setting were limited to the second half of the Juncker Commission (2016–2018) when Frans Timmermans headed the ROL portfolio: in those years, the Commission did propose some ROL legal bases and principles and – more clearly – repeatedly pushed the Court to make judicial innovations bite against recalcitrant governments. Yet proactive agenda-setting proved more of an exception than a rule and was not sustained over time.

The rest of the article proceeds in four sections. In Section 2 we propose a theoretical framework to study innovations by the ECJ and agenda-setting by the Commission, deriving alternative hypotheses for the links between the two in response to the EU's ROL crisis. In Section 3 we introduce the ECJ-ROL Dataset and provide descriptive statistics mapping the evolution of the Court's innovative ROL caselaw. In Section 4 we back-trace the Court's innovative ROL decisions to the Commission's observations and extra-judicial writings to demonstrate the inconsistent and limited scope of the Commission's agenda-setting influence. Finally, in Section 5 we place scope conditions on our findings and highlight how our analysis opens fruitful pathways for future research on the EU's ROL crisis and the politics of agenda-setting, judicial policy-making, and leadership in the EU.

2. Innovation, agenda-setting, and the rule of law

2.1. The court and judicial innovation

Innovative court rulings regularly feature in law and politics research in Europe and beyond (Alter & Meunier-Aitsahalia, Citation1994; Ovádek, Citation2023; Pavone, Citation2019; Vauchez, Citation2010, Citation2017). Yet, the concept of a ‘judicial innovation’ remains under-specified, and it is tempting to identify it following US Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart's famous quip about pornography: ‘I know it when I see it’ (Gewirtz, Citation1995, p. 1023).

Indeed, most scholars treat the ECJ's recent ROL decisions as self-evidently innovative even where they differ on the precise adjectives to describe them. Before 2010 the conventional wisdom amongst EU policymakers was that member states could organise domestic judiciaries however they pleased, the values of democracy and ROL enshrined in Article 2 of the Treaty on EU (TEU) were unenforceable, and the EU lacked the competences and tools to fight democratic backsliding (Emmons & Pavone, Citation2021; Kochenov, Citation2016; Kochenov & Pech, Citation2016). Then the ECJ flipped each presumption on its head. The Court broadened the EU's remit to intervene in ROL controversies, imposed novel obligations on member states to safeguard the ROL, and empowered the EU to sanction autocratizing governments and deprive them of EU funds (Ovádek, Citation2023; Scheppele & Morijn, Citation2023). Lawyers describe these rulings as being ‘as ground-breaking as [they are] surprising’ (Bonelli & Claes, Citation2018, p. 622); a ‘revolutionary case law’ (Kochenov & Bard, Citation2020, p. 276); ‘a ground-breaking turn in the history of EU law’ (Pech & Kochenov, Citation2021, p. 14); and a jolt to ‘the EU to further develop into a true “union based on the rule of law”’ (Van Elsuwege & Gremmelprez, Citation2020, pp. 31–32).

Clearly, the EU is undergoing a ‘constitutional moment’, spurred in great part by the ECJ's judicial innovations (Von Bogdandy et al., Citation2018). But not all of the Court's ROL decisions have been innovative. As we will show, the Court has adjudicated 96 ROL cases since 2010, only a subset of which broke new ground. To assess whether judicial innovations responded to the Commission's prodding, we need to avoid ‘conceptual stretching’ (Sartori, Citation1970) by distinguishing innovative from non-innovative decisions.

We theorise that judicial innovations comprise several dimensions. Consider three ECJ decisions often described as path-breaking. First, in its 2018 Portuguese Judges ruling,Footnote2 the Court first held that the democratic and ROL values in Article 2 TEU are justiciable when read in combination with member states' requirement under Article 19(1) TEU to maintain effective judicial protections (Ovádek, Citation2023, p. 13). Second, in its 2021 Repubblika judgment,Footnote3 the Court first established that EU law prohibits legislative reforms that ‘bring about a reduction in the protection of the value of the [ROL]…[or] any regression of their laws on the organisation of justice’. Third, in its Disciplinary Regime for Judges decision (2021),Footnote4 the Court first found that a member state (Poland) violated its obligation not to regress judicial protections under Article 19(1) TEU and ordered the suspension of a disciplinary body that could remove judges from their posts (Pech & Kochenov, Citation2021, p. 89).

These ECJ decisions make distinct innovations. Inter alia, Portuguese Judges establishes a new legal basis in EU primary law for supranational ROL enforcement (Art. 2 TEU + Art. 19(1) TEU). Repubblika creates a novel legal principle that guides ROL enforcement and imposes duties on member states (the principle of ‘non-regression’). And Disciplinary Regime for Judges gives teeth to these innovations by finding – for the first time – that a member state violated the non-regression principle and infringed Article 19(1) TEU.

These examples motivate our tripartite conception of judicial innovation. We define an innovative ROL decision as a ruling that does at least one of three things: (1) establishes a novel legal basis under EU primary law for ROL enforcement; (2) creates a novel legal principle to guide ROL enforcement; (3) makes these innovations bite for the first time by sanctioning a state for infringing a novel ROL legal basis or principle.

A clarifying word about how we use the term ‘legal principles’. ROL principles have been defined differently by EU primary law, the ECJ, and lawyers, catalysing a lively debate (Lenaerts & Gutiérrez-Fons, Citation2010; Tridimas, Citation2014; Von Bogdandy, Citation2010). For instance, whereas Article 2 TEU defines the rule of law as a ‘value’, the preamble of the Charter of Fundamental Rights refers to it as a ‘principle’. Whereas some EU scholars construe ‘non-regression’ as a principle (Pech & Kochenov, Citation2021), the Court's Repubblika judgment never directly defines it as such, while the ECJ's President conceives it as a ‘prohibition’ (Lenaerts, Citation2023, pp. 50–54). For clarity, we use ‘legal principles’ to denote logics of action derived from EU primary law that concretise obligations for member states and affordances for EU institutions. Novel ROL principles guide the EU to do something new with the EU Treaties to ensure that the values in Article 2 TEU are safeguarded by member states.

Our conceptual framework implies that the Court's ROL decisions can be uni- or multi-dimensionally innovative (by simultaneously establishing multiple innovations). It also implies that some innovations are more proactive than others (for instance, an enforcement action that simultaneously establishes a new legal basis is more proactive than the first enforcement of a previously-established legal basis). Further, the Court can build its caselaw to shift the locus of innovation over time. During its ‘founding period’ in the 1960s–1970s (Phelan, Citation2019), the Court developed a teleological approach for ‘revolutionising European law’ that first created legal bases and principles and then moved to their enforcement (Rasmussen, Citation2014). In the economic field, the Court established Article 30 TFEU (prohibiting customs duties and charges) as the legal basis for dismantling trade barriers, then created principles to orient enforcement (ex. the principle of ‘mutual recognition’), and then struck down national laws (Maduro, Citation1998). As we will see, the ECJ has revived this teleological approach in the ROL field.

2.2. The commission and judicial agenda-setting

Having conceptualised judicial innovation by the Court, how might we theorise agenda-setting by the Commission?

Existing research focuses on the primary means for the Commission to influence ECJ decisions: lodging cases and filing observations before the Court. First, as ‘guardian of the Treaties’, the Commission is the sole EU institution empowered (under Article 258 TFEU) to take noncompliant states to Court by launching infringement proceedings and seeking penalty payments for continued violations (Article 260 TFEU) (Falkner, Citation2018; Fjelstul & Carrubba, Citation2018; Hofmann, Citation2013; Kelemen & Pavone, Citation2023; Tallberg, Citation2002). Second, the Commission consistently files observations in cases referred to the ECJ by national courts, known as ‘preliminary references’ under Article 267 TFEU (Krehbiel & Cheruvu, Citation2022; Pavone & Kelemen, Citation2019; Stone Sweet & Brunell, Citation2012).Footnote5 We call this the direct path of judicial agenda-setting, and it has frequently been mobilised by the Commission to spur judicial innovations. To cite one well-known example, the Commission's Legal Service developed the principle of the direct effect of EU law in 1961–1963 and then successfully invited the Court to embrace this innovation in its observations in the Van Gend en Loos (1963) case (Rasmussen, Citation2014; Vauchez, Citation2010).

Yet, the Commission can also wield an indirect path of agenda-setting by publishing reports and commentaries that are read by the Court. The ECJ is a porous institution whose members scout beyond court proceedings for innovative ideas (Stein, Citation1981; Weiler, Citation1994). The Court not only pays attention to Commission reports and law journal commentaries that ‘provide legitimacy to [a] new jurisprudence’ (Byberg, Citation2017, p. 46), but ECJ judges also ‘read the morning papers’ (Blauberger et al., Citation2018). To be sure, assessing the influence of extrajudicial writings is challenging: ECJ rulings never cite these materials. However, Advocates General (AGs) – ECJ members who propose how their colleagues should decide cases (Tridimas, Citation1997) - often reference extra-judicial writings in their opinions (Makszimov, Citation2023). Crucially, AGs often act as change entrepreneurs (Solanke, Citation2011) and their opinions are followed by the Court 70 to 90 percent of the time (Arrebola et al., Citation2016, pp. 85–91). Commission officials thus acknowledge that they pen articles to ‘influence the Court's work…through the opinions of Advocates General’ by targeting journals favoured by ECJ judges (Leino-Sandberg, Citation2021, Citation2022, p. 246). During the first five years of the ROL crisis, Commission lawyers penned 23 articles in the Common Market Law Review and the European Law Review promoting the Commission's agenda (Leino-Sandberg, Citation2022, p. 247).

2.3. Linking judicial innovation and agenda-setting

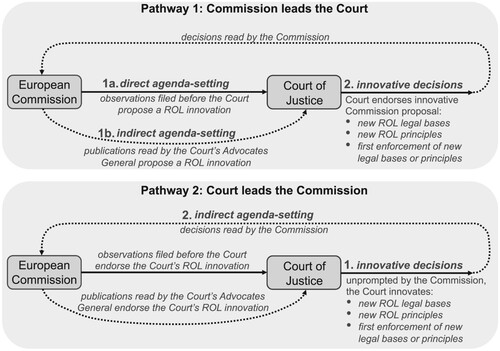

How can we theorise the possible links between the Court's innovative ROL decisions and Commission agenda-setting? We derive three alternative hypotheses from existing research and map their observable implications in .

Our first hypothesis (H1) – the Commission leads the Court - draws from a strand of classic supranationalist theory (Hofmann, Citation2013; Pollack, Citation1998; Snyder, Citation1993; Stone Sweet, Citation2004) stressing that ‘the Court [is] guided by the Commission in the direction of greater legal integration’ (Maduro, Citation1998, p. 9). Although supranationalist accounts treat the Commission and the Court as ‘partner[s] in constructing judicial and supranational authority’, most also highlight that the Commission possesses a first-mover advantage as the ‘supranational nerve centre of the [EU] system’, Stone Sweet (Citation2004, p. 47) with the ECJ ‘respon[ding] to the briefs of the Commission’ (Stone Sweet & Brunell, Citation2012). If these supranationalist theories generalise to the ROL field, we would expect the Commission to mobilise as a judicial agenda-setter to bolster the EU's ROL competences (the upper path in ). As Hooghe and Marks (Citation2019, pp. 1125–1126) put it, this view ‘alerts one to the supranational activism of the Commission’ in responding to the ROL crisis, underscoring how the ‘Commission asked the [ECJ] to suspend’ national laws ‘to exert pressure on illiberal states’ and ‘develo[p] new channels of [EU] influence’ (see also Pircher, Citation2023, pp. 774–775). The implication, then, is that the Commission should proactively file observations, lodge infringements, and pen writings proposing innovations that the Court then adopted.

Our second hypothesis (H2) – the Court leads the Commission – draws on postfunctionalist and new intergovernalist arguments positing a decline in the Commission's agenda-setting influence (Hodson, Citation2013; Kreppel & Oztas, Citation2017) in response to a politically constraining intergovernmental climate (Bickerton et al., Citation2015; Hooghe & Marks, Citation2009). These accounts do not expect the Commission to act as a supranational entrepreneur in politically contentious and sovereignty-constraining fields like ROL enforcement. Instead, they expect the Commission to heed persistent member state resistance by dragging its feet and forbearing from judicial agenda-setting (Closa, Citation2019; Kelemen, Citation2023; Kelemen & Pavone, Citation2023). Some scholars are even repurposing Court-centric supranationalist theories (ex. Burley & Mattli, Citation1993; Tallberg, Citation2000) by arguing that the less politically-constrained ECJ issued innovative ROL decisions precisely as a desperate attempt to jolt the Commission to act (Kochenov & Bard, Citation2020; Ovádek, Citation2023; Scheppele, Citation2023; Scheppele et al., Citation2020). If this account is right, we would expect judicial innovations to be unprompted by the Commission; the Commission's interventions should merely endorse the Court's pre-existing caselaw (the lower pathway in ).

Our final hypothesis (H3) is that the reins of leadership shifted over time from the Court to the Commission. This account builds on research positing that while the Commission initially stalled in responding to the ROL crisis, it reclaimed its role as supranational entrepreneur once the political climate became more supportive. As the Hungarian and Polish governments obstructed intergovernmental agreements beyond the ROL field and marginalised themselves in the Council beginning in 2020 – by threatening to torpedo the EU budget, passing anti-LGBTQ laws, and holding up aid to Ukraine – member states signalled growing support for vigorous and creative ROL enforcement. For instance, member states increasingly filed supportive observations in ROL infringements and the Council endorsed the Commission's proposed suspension of €6.3 billion in EU funds to Hungary under the ROL Conditionality Regulation (Blauberger & Sedelmeier, Citation2024; Hernández & Closa, Citation2023; Priebus & Anders, Citation2023; Scheppele & Morijn, Citation2023; Winzen, Citation2023). We would thus expect a change over time (a shift from the lower to the upper path in ): The Court's innovative ROL decisions should be unprompted by the Commission pre-2020 and become responsive to an uptick in innovative Commission proposals post-2020.

3. Mapping judicial innovations in rule of law cases

3.1. The ECJ-ROL dataset

To adjudicate the explanatory purchase of the foregoing hypotheses, we built a new dataset of all ROL cases adjudicated by the Court: The ECJ-ROL Dataset. We first identified the universe of ROL cases and the subset of cases with judicial innovations (new legal bases, new principles, or their first enforcement) to map variation in our outcome of interest. Once we identified a judicial innovation in a given case, we then back-traced through all prior decisions points within that case and across preceding cases to assess whether the Court responded to a innovative Commission proposal. To this end, we disaggregated ROL cases into timestamped sequences of decisions matched with the Commission's observations, infringement applications, and extra-judicial writings.

Identifying the universe of ROL cases is more challenging than it seems. The Court's caselaw database (curia.europa.eu) does not capture ‘ROL cases’ – variously classifying these as ‘social policy’, ‘fundamental rights’, or ‘non-discrimination’ cases. Using these subject matter labels risks capturing irrelevant cases and omitting relevant ones. We thus adopted a case selection strategy that triangulates between the expertise of a diverse cohort of EU legal scholars. We selected four authoritative legal sources chronicling ROL enforcement in the EU: the ROL Dashboard by the Meijers Committee (Meijers Committee, Citation2023), the Swedish Institute for European Policy Studies' (SIEPS) ROL casebook (Pech & Kochenov, Citation2021), the book EU Values Before the Court of Justice (Spieker, Citation2023), and a recent overview of the ECJ's ROL caselaw by the Court's President, Koen Lenaerts (Lenaerts, Citation2023)'. These four sources capture distinct expert perspectives. The Meijers Committee is an independent standing committee of jurists and policymakers in the Netherlands chronicling ROL cases before the ECJ; SIEPS is an independent research institute in Sweden that commissioned a widely-cited casebook on the ECJ's ROL caselaw by two leading scholars; Spieker (Citation2023) constitutes the most recent and comprehensive academic text tracing the Court's enforcement of EU values; and Lenaerts (Citation2023) captures the Court's own itinerary of its ROL caselaw. To be as comprehensive as possible, any case cited by one of these authoritative legal sources is included in the ECJ-ROL Dataset, yielding 120 cases total. 96 of these cases were lodged since 2010 – the temporal focus of our analysis.

We then parsed and coded each ROL case on several dimensions to back-trace the locus of each judicial innovation. Each case is disaggregated into timestamped decisions (by the Court and parties to each case, including the Commission) with various substantive attributes (such as the legal bases or ROL principles cited). After all, each ECJ ‘case’ unfolds in regularised steps (lodging or referring the case, submitting observations, delivery of AG opinions, interim orders, and final judgments) wherein each step provides an opportunity for proposing or establishing a ROL innovation. We developed a new python algorithm to capture and date when the Court cited a new legal basis combination (LBC) under the Treaties (for instance, Art. 19 TEU + Art. 2 TEU) to adjudicate a dispute or establish that a state breached its obligations, and used keywords to manually code when the Court established innovative ROL principles (such as ‘regression’ for the principle of non-regression; more details below). We proceeded likewise to code Commission observations and AG opinions citing the Commission's extra-judicial writings.

To build the ECJ-ROL Dataset, we collected hitherto confidential data and integrated it with public information from three data sources. We first drew information from the two largest databases on ECJ cases, the Curia and the EUR-Lex websites. Since these sources omit the Commission's observations, we filed dozens of Freedom of Information (FOI) requests to the Commission's Legal Service and obtained all hitherto confidential Commission observations in closed ROL cases. We also incorporated data from the IUROPA Database Platform (Brekke et al., Citation2023), which includes unique identifiers for all decisions in ECJ cases, using the R-Package created by Fjelstul (Citation2023). We scraped any missing information using the R-package developed by Ovádek (Citation2021) and then triangulated between the plain text, Curia, and EUR-LEX versions of each decision.

3.2. Revealing patterns

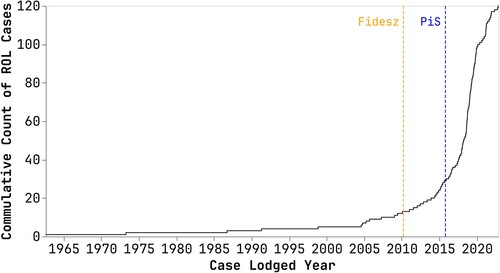

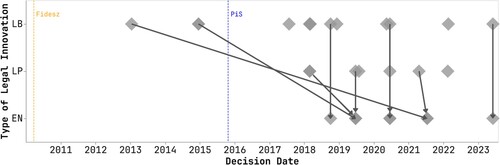

Using the ECJ-ROL Dataset, we can visualise revealing patterns of ROL cases and judicial innovation. To begin, there is a striking spike in demand for the ECJ to resolve contentious ROL disputes after 2010 and 2015 - when the newly-elected Fidesz and PiS governments in Hungary and Poland respectively began to systematically dismantle democracy and the ROL. maps the cumulative distribution of ROL cases: whereas the ECJ only adjudicated a trickle of ROL cases for the first five decades of its existence (n = 24 from 1965 to 2010), since 2010 the number of ROL cases has grown exponentially (n = 96).

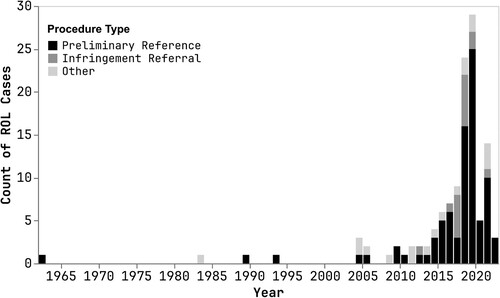

If we distinguish ROL cases by procedure type, another suggestive finding emerges: how seldom the Commission has exercised a key agenda-setting power as ‘guardian of the Treaties’. demonstrates that the vast majority of the Court's ROL cases are preliminary references punted by national courts (in black) rather than infringements referred by the Commission (in medium grey). While supranationalist accounts stress the Commission's eagerness to wield its discretion to launch infringements against member states, infringements make up a tiny share of the ECJ's ROL caseload. In fact, for the first six years of the EU's ROL crisis, the Commission only referred two ROL infringements to the Court, consistent with a pattern of ‘forbearance’ (Kelemen & Pavone, Citation2023).

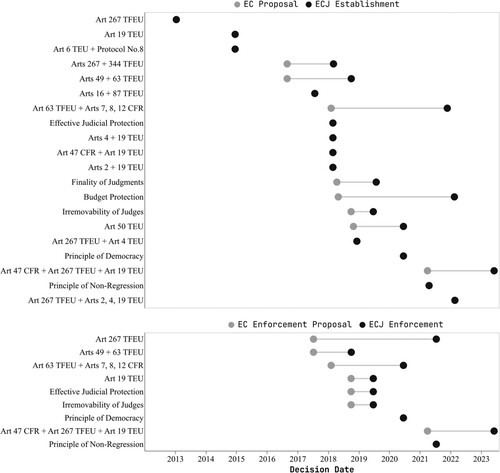

Not all ROL cases break new ground. Focusing on ECJ rulings delivered in the 96 cases lodged since 2010, only 16.7% (n = 16) of the cases contained at least a novel legal basis, a new ROL legal principle, or the first enforcement of a new legal basis or principle against a member state. Parsing these 96 cases into 180 decision points, only 16.1% (n = 29) of these established a ROL innovation: 14 new legal basis combinations (LBCs), 6 new legal principles, and 9 innovative enforcement actions.Footnote6 As the Court innovates and develops its ROL caselaw, it appears to be redeploying the teleological approach it wielded to revolutionise EU law in decades past (Rasmussen, Citation2014). zooms-in on innovative ROL decisions delivered since 2010. Notice how the Court tends to first identify novel legal bases in the Treaties to bolster the EU's competences in ROL enforcement, followed by establishing ROL principles to interlink legal bases with concrete ROL enforcement actions, and then making these innovations ‘bite’ by sanctioning states in infringement cases.

Figure 4. The teleological development of the Court's ROL innovations..

Note: LB = new legal basis, LP = new legal principle, EN = first enforcement of new LB or LP

These graphs help us visualise patterns of judicial innovation and confirm that the Commission has been sparing in generating ROL-cases before the Court using its enforcement powers. Yet these data are insufficient for probing whether and when the Court's ROL innovations responded to direct and indirect agenda-setting by the Commission. To adjudicate the relative explanatory purchase of H1, H2, and H3, we need to work backwards and trace each judicial innovation to its source.

4. Tracing commission agenda-setting using the ECJ-ROL dataset

From 2010 to 2023, the ECJ established 29 judicial innovations in 16 ROL cases. We begin by asking: how many innovations were prompted by direct Commission agenda-setting?

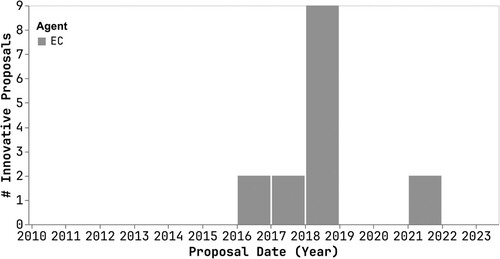

Working backwards using the ECJ-ROL dataset, we found that half of these ROL innovations – 15 of 29 (51.7%) – were preceded by innovative proposals that the Commission filed before the Court. In the other instances, the ECJ crafted judicial innovations unprompted, often spurring the Commission to act. The Commission also proved an inconsistent agenda-setter. As captures, the Commission spearheaded innovative proposals almost exclusively during the second half (years 2016–2018) of the Juncker Commission (86.7% of all proposals). Furthermore, the Commission proved more eager to prompt the latter stages of the Court's innovation process: the Commission proposed only 35.7% (5/14) of innovative LBCs and 50% (3/6) of new legal principles established by the Court, but it proposed most (77.8%, or 7/9) of the ECJ's innovative enforcement actions. Because the Commission more often intervened to enforce judicial innovations than to establish them, its agenda-setting was more reactive than is apparent at first glance.

As we elaborate below, our findings demonstrate that supranationalist accounts of the Commission as a vigorous judicial agenda-setter (H1) do not generalise to the ROL field. With the exception of the more proactive latter years of the Juncker Commission when Vice President Frans Timmermans took charge of the ROL portfolio (Dinan, Citation2016), the ‘guardian of the Treaties’ was a predominantly indifferent – and occasionally obstructive – agenda-setter. Instead, our analysis sits as a hybrid of H2 and H3. In line with H2, the Court often had to spur a reluctant Commission to act via innovative rulings; in line with H3, the 2016-2018 period marked a temporary shift to more proactive agenda-setting, however one that was not sustained over time. To enable scrutiny of these inferences, we compiled our coding and relevant textual excerpts for all cases and innovations in a transparency appendix (Moravcsik, Citation2014), along with replication files for all our data and figures.

4.1. Establishing new ROL legal bases: foot-dragging and inconsistency

Leveraging our python algorithm, we identified fourteen new LBCs established by the Court to expand and constitutionalise the EU's ROL competences in EU primary law. The first innovative LBC dates back to the Court's Križan ruling in January 2013, followed by three new LBCs established in two Opinions of the Court, Adhésion de l'Union à la CEDH (2014) and Accord PNR UE-Canada (2017). These four LBCs for ROL enforcement were established prior to the landmark Portuguese Judges ruling in 2018 (Ovádek, Citation2023),Footnote7 although the majority of innovative LBCs followed in its wake- see .

Table 1. Establishing new ROL legal bases.

To back-trace whether the Commission inspired the development of these new LBCs, we scrutinised all of the Commission's written observations and infringement referrals in all ROL cases up until the judgment dates in . We found that the Commission was silent or indifferent to the establishment of seven new LBCs, obstructed the establishment of two, and successfully proposed the establishment of four (and partly proposed a fifth). On balance, the evidence showcases a Commission reluctant to propose novel LBCs, whose indifference was punctured by occasional obstruction and some innovative proposals primarily spreadheaded from 2016 to 2018.

First, we found that the Commission was silent in the lead-up to the Court's establishment of seven new LBCs. To illustrate this we present two cases. In the 2013 Križan and Others ruling, the ECJ established that under Art. 267 TFEU, national courts cannot be precluded from ‘bringing the matter before the Court of Justice’ even when the parties did not explicitly raised a point of EU law in the proceedings.Footnote8 This innovation was not prompted by any proposal in the Commission's observations. Next, in its July 2013 observations in Adhésion de l'Union à la CEDH, the Commission acknowledged both Art. 6 TEU + Protocol No.8 and Art. 19 TEU, but did not argue that the Court should establish them as constitutional backstops. Again, it was the ECJ that constitutionalised this new LBC via an innovative ruling.Footnote9 We noted similar patterns for all remaining LBCs wherein the Commission either remained silent or referenced the LBCs only in passing, without advocating that the Court valorise or establish them as a basis for EU ROL enforcement.

Second, we uncovered two instances where the Commission obstructed the establishment of new LBCs.Footnote10 In its May 2016 observations in the Portuguese Judges case, the Commission obstructed the establishment of Art. 19 TEU + Art. 47 CFR by arguing that the Court ‘manifestly lacked jurisdiction’ (‘manifestement incompétente’) to answer the questions referred by the Portuguese Supreme Administrative Court invoking those very legal bases. This argument was rejected by the Court as it established the justiciability of this new LBC in its judgment.Footnote11 And in its observations on May 2019 in A.B. and others, the Commission obstructed the establishment of Art. 267 TFEU + Art. 2, 4, 19 TEU, arguing instead for a sole interpretation of Art. 19 TEU and casting the inclusion of Art. 267 TFEU, and Art. 2, 4 TEU as ‘superfluous’. This logic was partially followed by the Court, until it established this new LBC in its RS judgment (2022).Footnote12

Despite the prevailing indifference and occasional obstruction presented above, the Commission did promote the establishment of four new LBCs (and partially promoted a fifth). Beginning with its August 2016 observations in the Achmea case, the Commission proposed that an arbitration clause in a bilateral investment treaty (BIT) was incompatible with the joint application of Art. 267, 344 TFEU + Art. 19 TEU. The Court almost fully endorsed the Commission's proposal, establishing a new LBC comprised of Art. 267 and 344 TFEU while discarding Art. 19 TEU.Footnote13 In the same observations, the Commission proposed another judicial innovation – the joint establishment of Art. 49 TFEU + Art. 63 TFEU – however it was not taken up by the Court until the Commission proposed the innovation a second time in Commission v. France (2018).Footnote14 In its November 2018 observations in the Wightman case, the Commission proposed an innovative constitutional interpretation of Art. 50 TEU that was subsequently endorsed the Court in the same case.Footnote15 In August 2018, the Commission lodged an innovative infringement referral on the joint basis of Art. 63 TFEU + Art. 7, 8, 12 CFR, a new LBC that was then enshrined by the Court in its June 2020 judgment.Footnote16 Our final example of a successful Commission proposal followed a sudden change of heart. In its observations on March 2020 in the IS case, the Commission initially obstructed the establishment of Art. 47 CFR + Art. 267 TFEU + Art. 19 as a new LBC by arguing that the case should be deemed inadmissible. Yet one year later in April 2021 – while the Court's IS ruling was still pending – the Commission lodged an infringement referral against Poland on the basis of the very LBC it had rejected in ISFootnote17. The Commission proposed the new LBC anew in September 2021 (in RS), prompting the Court to come around and established the new LBC until its June 2023 Commission v Poland ruling.Footnote18

The foregoing evidence highlights a reluctant and inconsistent Commission that played little role in the establishment of most of the new LBCs wielded by the Court to expand the EU's competences in ROL matters. The Commission did propose a few innovative LBCs from 2016 to 2021, but these proposals were characterised by about-turns and filed at the same time that the Commission was dragging its feet and obstructing innovations in parallel cases. If the Commission had a master plan to expand the EU's competences by proposing new legal bases for ROL enforcement, this strategy is hardly discernible across its observations before the Court.

4.2. Establishing new ROL principles: agenda-setting as a two-way street

From 2018 to 2023, the ECJ established new principles to guide EU ROL enforcement and impose Treaty obligations upon member states. Triangulating among four authoritative legal sources described previously, we found that they identified six new principles:

Effective judicial protection: states are ‘obliged’ to ensure that their courts are sufficiently independent to safeguard individual rights.Footnote19

Irremovability of judges: states are ‘required’ to protect courts from ‘all external intervention or pressure’ and ensure that competent judges ‘remain in post’.Footnote20

Finality of judgments: states are prohibited from allowing a ‘final, binding judicial decision to remain inoperative to the detriment of one party’ via noncompliance.Footnote21

Democratic pluralism: states must protect ‘freedom of association’ and citizens' capacity ‘to act collectively’ as an essential basis ‘of a free and democratic society’.Footnote22

Non-regression: states are ‘required to ensure that…any regression of their laws on the organisation of justice is prevented’.Footnote23

ROL as a basis for budget conditionality: Since the ROL is ‘part of the very foundations of the [EU]’, it can ‘constitut[e] the basis of a [budget] conditionality mechanism’Footnote24

Back-tracing whether the Commission pushed the Court to enshrine these principles, our findings reveal an inconsistent Commission that only played a clear agenda-setting role in proposing two of six ROL principles (and indirectly proposed a third) – see . On balance the Commission's interventions tended towards indifference, except for a moment of innovation in 2018. Agenda-setting thus proved a two-way street: the Court was as likely to mobilise the Commission as the reverse.

Table 2. Establishing new ROL principles.

First, we found no evidence that the Commission proposed the principle of non-regression. The Commission did on two occasions factually acknowledge a ‘regression’ in the independence of the Romanian judiciary (in C-83/19, Romanian judges, and C-379/19, PM), but it never gave this concept a normative thrust. The Commission also did not wield its observations to propose that the Court adopt a principle that the ROL serves as a basis for budget conditionality – a principle the ECJ affirmed in 2022Footnote25 once Hungary and Poland unsuccessfully challenged the legality of the ROL Conditionality Regulation. To be fair, the Commission did indirectly promote this judicial innovation by proposing the Regulation in 2018, creating an opportunity for the Court to legitimate it Priebus and Anders (Citation2023).

Second, the Commission missed opportunities to spur judicial innovations despite signals from the Court that it would eagerly seize them. Consider the principle of democratic pluralism. Intermittently in its observations, the Commission cited Article 2 TEU holding that the EU ‘founded on the values of…democracy…[and] pluralism’, but it failed to develop it into a binding legal principle. For instance, when the Commission brought an infringement challenging a 2017 Hungarian ‘LexNGO’ reform stigmatising pro-democracy NGOs, it did not invoke the democracy provisions of Article 2 TEU. As ECJ President Lenaerts lamented, because ‘the Commission did not refer to that Treaty provision’ and the democratic ‘values it underpins’, the Court could not invoke it in its ruling against Hungary (in C-78/18, Commission v. Hungary). Nevertheless, the ECJ creatively leveraged the case to articulate a principle of democratic pluralism ‘implicitly’ linked to Article 2 (Lenaerts, Citation2023, p. 27). Only after the Court's prodding did the Commission mobilise Article 2 and the principle of democratic pluralism (Vissers, Citation2023).

Third, the Commission obstructed the development of the principle of effective judicial protection. The ‘right…to effective judicial protection’ was first invoked by the French Constitutional Council in a 2013 referral to the ECJ (C-168/13 PPU, Jeremy F). The Commission acknowledged the referral but did not elaborate the notion of effective judicial protection. In subsequent preliminary references invoking effective judicial protection, the Commission framed it as an unenforceable or subordinated it to countervailing principles. For instance, in the Achmea case (C-284/16) concerning the compatibility of bilateral investment treaties (BITs) with EU law, the Commission reversed its longstanding support of BITsFootnote26 and subordinated effective judicial protection to mutual trust: Since ‘one of the premises of EU law is that each Member State trusts the effective judicial protection assured…by other Member States’, arbitration clauses to ensure judicial protection violate ‘the principle of mutual trust’. And in Portuguese Judges, where the Portuguese Supreme Administrative Court invoked the principle of effective judicial protection to challenge judicial salary cuts, the Commission (unsuccessfully) countered that the ECJ should declare the referral inadmissible: since EU law leaves such ‘a large margin of appreciation to member states’ in budgetary matters, judges cannot challenge salary reductions by invoking effective judicial protection. The ECJ disagreed, holding the referral admissible and declaring that the principle of effective judicial protection binds member states, ‘finally convinc[ing] the Commission to launch infringement actions directly on the basis of Article 19(1) TEU’ (Ovádek, Citation2023; Pech & Kochenov, Citation2021, p. 29).

Despite the above evidence of foot-dragging and even obstruction, the Commission did have spurts of innovation, prompting the development of the principles of finality of judgments and irremovability of judges. Yet these interventions all occurred in 2018, belying a ‘fundamental’ shift to a more assertive stance.

In September 2015, the Hungarian government passed a law prohibiting administrative courts from modifying the decisions of immigration officials. Henceforth administrative courts could only annul the decisions of the Immigration Office, whose officials repeatedly ignored judicial rulings annulling decisions denying asylum. When the administrative court of Pecs referred a case to the ECJ, the Commission seized the opportunity. In its April 2018 observations interpreting the right to a fair trial (under Article 47 of the Charter) in light of the case law of the European Court of Human Rights, the Commission proposed that a fair trial ‘would be illusory if one of the member States allowed a final and obligatory judgment to remain unimplemented to the detriment of one party’. A year later, the ECJ adopted the Commission's proposed principle almost verbatim.Footnote27

Finally, in September 2018 the Commission argued that Poland ‘infringe[d] the principle of security of tenure of judges’ when it passed a law lowering the retirement age of sitting Supreme Court judges and empowering the Polish President to control the extension of judges' mandates. The ECJ agreed: highlighting how the Commission ‘submit[ted] that, by thus lowering the retirement age…[Poland] infring[es] the principle of the irremovability of judges’, the ECJ elaborated the principle, specified its requirements under Article 19(1) TEU, and held that ‘there can be no exceptions to that principle unless they are warranted by legitimate and compelling grounds’.Footnote28

4.3. Making innovations bite: reactive or proactive enforcement?

While new LBCs and principles constitutionalised the ROL in the EU, they risk remaining paper laws unless they are mobilised against member states that breach them. The Commission can play a crucial role in making judicial innovations ‘bite’ by lodging infringements against member states and referring these cases to the ECJ. To what extent has the Commission pushed the first enforcements of new LBCs and principles, and has it acted more proactively or reactively?

To answer, we scrutinise all 9 instances across 5 cases where the ECJ first found a member state liable for breaching a new LBC or principle. Analysing the Commission's infringement applications and observations in these cases, we back-traced whether the Commission invoked new LBCs or principles in its infringement referrals, and whether it proactively proposed these very innovations or reactively sought to enforce those pre-established by the Court.

demonstrates that although the Commission has been sparing in lodging ROL-related infringements before the Court, when it does it plays an important role in spurring innovative enforcement actions. Of the nine times that the ECJ first found a breach of a new LBC or principle, seven (77.8%) were proposed by the Commission (‘P’ in ). At the same time, the Commission has been more reactive than proactive. The Commission is more keen to propose the enforcement of innovations that were already established by the Court: only four times did the Commission propose that the Court simultaneously establish and enforce a novel LBC or principle (denoted by the asterisk (*) in ). And with only one exception (for C-204/21), all proposals to make judicial innovations bite were limited to a couple of years period from 2017–2019.

Table 3. Making judicial innovations bite for the first time.

When it comes to making new LBCs bite, in two of five instances the Commission invoked LBCs previously established by the Court. Further, in both of these instances the Commission dragged its feet. Art. 267 TFEU and Art. 19 TEU were established as ROL legal bases by the ECJ in Križan (2013) and Adhésion de l'Union à la CEDH (2014) absent any proposal or prodding by the Commission. It took four and six years, respectively for the Commission to finally ask the Court to make these LBCs bite in response to the Polish government's political takeover of the judiciary (in its October 2019 and October 2018 infringement referrals in C-791/19 and C-619/18). In three other instances, however, the Commission proved more proactive. Art. 49 TFEU + Art. 63 TFEU, Art. 63 TFEU + Art. 7, 8, 12 CFR and Art 47 CFR + Art 267 TFEU + Art 19 TEU were established as new LBCs by the Court in Commission v France (2018), Commission v Hungary (2018), and Commission v Poland (2023) respectively. In these cases, the Commission had proposed that the Court establish the very legal bases that the judges then deployed to find a member state liable for breaching EU law.

A similar pattern emerges when scrutinising the first four enforcements of new ROL principles. In two of these instances, it was the Court that had to creatively reframe narrowly-tailored Commission infringements to make ROL principles bite. In November 2019, the Commission lodged an infringement against Poland proposing that a bundle of legal provisions creating a disciplinary chamber to sanction judges constituted a ‘structural break’ undermining judicial independence.Footnote29 Yet, the Commission did not link this ‘break’ to a broader notion that member states are prohibited from dismantling their justice systems in ways that will systematically reduce the protection of the ROL. It was the ECJ that seized this narrowly-tailored infringement and amplified it into the first violation of the principle of non-regression in Commission v Poland (2021). The Court took even more liberties in wielding a narrow infringement lodged by the Commission against Hungary's anti-NGO reforms (on non-democracy grounds) to find the first violation of the principle of democratic pluralism in Commission v Hungary (2020) (Lenaerts, Citation2023). In the other two instances, however, the Commission did mobilise as an agenda-setter. After unsuccessfully obstructing the ECJ from establishing a sweeping principle of effective judicial protection in Portuguese Judges (2018), the Commission pivoted: Six months later it referred an infringement to the ECJ successfully arguing for the first time that Poland committed ‘irreparable damage for the principle of effective judicial protection’ by undermining the independence of the Supreme Court.Footnote30 And in 2019 when the ECJ found that the Polish government violated the principle of irremovability of judges, it responded to the Commission's proposal that the Court simultaneously establish and enforce that very principle.

In sum, the Commission has more consistently played an agenda-setting role in proposing the enforcement (rather than the establishment) of new legal bases and ROL principles. Yet with a few notable exceptions in 2017 and 2018, even the Commission's enforcement actions followed in the Court's wake: the ‘guardian of the Treaties’ is more comfortable walking through the threshold if the Court has already opened the door. To visualise these findings, displays a timeline mapping when the ECJ established novel ROL legal bases, legal principles, and enforcement actions (in black) and which of these innovations can be traced to prior proposals that the Commission submitted before the Court (in grey).

4.4. The absence of indirect agenda setting

All the evidence hitherto presented concerns the direct path of agenda-setting: observations and applications by the Commission before the Court. But the Commission might also inspire judicial innovations indirectly, when it (or its officials) craft reports and commentaries cited by the ECJ's Advocates General (AG) to propose ROL innovations. As ECJ President Lenaerts has acknowledged, AGs have played an important role in shaping the ECJ's thinking in ROL matters (Lenaerts, Citation2023, pp. 41, 54–55). Is there any evidence of Commission influence via this indirect path?

To answer, we scrutinised all 91 AG opinions delivered in ROL cases adjudicated by the ECJ since 2010. These opinions include 385 extra-judicial citations, and we were able to identify the author affiliations of 75% (n = 288) of these cited documents. The results reveal a striking absence: Only 18 of these 288 cited documents (6.3%) were penned by the Commission or its officials, and none of these were cited by AGs to propose a judicial innovation. This does not mean that indirect agenda-setting could not have played a more important role. For instance, AG Bobek's opinion delivered in March 2021 in criminal proceedings against PM (C-357/19) cited two Commission reportsFootnote31 to discuss the principle of finality of judgments, but that principle had already been established two years prior. While AGs sometimes wield the Commission's extrajudicial writings to buttress their calls for judicial innovations (Leino-Sandberg, Citation2021, p. 246), there is no evidence that this dynamic contributed to the ECJ's ROL revolution.

5. Conclusions and pathways for future research

In this article, we developed a new theoretical framework to study judicial innovations and supranational agenda-setting in the EU. We then deployed this framework to analyse an original dataset of all ROL cases before the ECJ (the ECJ-ROL Dataset) and adjudicate amongst alternative explanations for the Court's innovative decisions. We found that the Commission has not been the vanguard propelling a revolution in the ECJ's ROL caselaw. The Commission did propose several ROL innovations adopted by the Court, but proactive agenda-setting proved intermittent, inconsistent, and limited primarily to the 2016-2018 period. Outside this period the Commission's default stance was indifference, and it was the Court that tended to mobilise the Commission via innovative rulings. These findings contradict supranationalist accounts of the Commission as a stalwart judicial agenda-setter, revealing a haphazard ‘guardian of the Treaties’ that has neither ubiquitously dragged its feet nor seized the mantle of leadership.

Although our findings do not neatly align with the expectations of existing research, they are consistent with anecdotal evidence that leadership shifts within the Commission matter (Müller, Citation2019; Tömmel & Verdun, Citation2017), especially in response to crises and contentious issues that sow divisions within the Berlaymont (Hooghe, Citation2001; Mérand, Citation2021). The Commission was most proactive as a ROL agenda-setter during Frans Timmermans' influential mandate as first Vice-President of the Juncker Commission charged with the ROL portfolio (Dinan, Citation2016). As Scheppele (Citation2023, p. 125) notes, Timmermans ‘was clearly personally committed to fighting for the [ROL]…he pushed the issue as hard as he could’, even if the Presidency and other Commissioners did not always ‘allow him to run with the brief’ (see also Closa, Citation2019). When Timmermans ran for the Commission Presidency, the Hungarian and Polish governments successfully rallied opposition to his candidacy, ‘no doubt a signal’ that too proactive a ROL stance ‘could have negative consequences’ (Scheppele, Citation2023, p. 125). When Ursula von der Leyen succeeded Juncker as Commission President, Timmermans was moved off the ROL portfolio. Future research could deepen the causal links between these leadership shifts and the Commission's behaviour as a judicial agenda-setter.

There are scope conditions to our findings. Since we focussed on scrutinising the Commission's agenda-setting influence, we did not probe whether other actors – such as referring national courts or private litigants and their lawyers (Mayoral & Torres Perez, Citation2018; Pavone, Citation2022) – inspired some of the ECJ's ROL innovations. We should not conclude from the absence of innovative Commission proposals that the Court devised innovations out of thin air. Future research could leverage the ECJ-ROL dataset to probe whether other parties influenced the Court's ROL agenda. Finally, since we sought to explain the source of judicial innovations, we did not consider the important role played by the Commission as a legislative and policy agenda-setter, particularly in suspending EU funds to Hungary and Poland (Blauberger & Sedelmeier, Citation2024; Hernández & Closa, Citation2023; Kelemen, Citation2024; Scheppele & Morijn, Citation2023). The road to EU budget conditionality clearly attracted much of the Commission's attention. Yet these developments would not have been possible without the Court bolstering the EU's ROL competences and imposing a growing set of ROL obligations upon member states. And it is unlikely that the Court is done with its work. As a wave of democratic backsliding shows signs of stalling and member states like Poland seek to reverse autocratization (Matthijs, Citation2023), scholars will have a unique opportunity to trace if and how the ECJ reorients its caselaw to support the restoration of liberal democracy.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (1.7 MB)Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful for comments received at the 2023 ARENA Centre for European Studies staff seminar, the 2023 Enforcing the Rule of Law in the EU (ENROL) Advisory Board meeting, and the thoughtful feedback provided by Daniel Naurin, Kim Scheppele, R. Daniel Kelemen, Petra Bard, Natasha Wunsch, Christophe Hillion, three anonymous reviewers and the special issue editors. Any remaining errors or omissions remain our own responsibility.

Data availability statement

Replication data and code for this article can be found https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2024.2336125.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mauricio Mandujano Manriquez

Mauricio Mandujano Manriquez is a PhD Fellow at the ARENA Centre for European Studies of the University of Oslo.

Tommaso Pavone

Tommaso Pavone is Assistant Professor of European politics in the Department of Political Science at the University of Toronto and Visiting Researcher at the ARENA Centre for European Studies at the University of Oslo.

Notes

1 The Commission can also submit its observations in cases brought by one member state against another member state under Art. 259 TFEU, but these are exceptionally rare.

2 C-64/16, Portuguese Judges [2018] ECLI:EU:C:2018:117.

3 C-896-19, Repubblika [2021] ECLI:EU:C:2021:311, at pars. 63–64

4 C-791/19, Commission v. Poland [2021], ECLI:EU:C:2021:596

5 See Footnote 1.

6 Legal basis combinations may exist as stand-alone legal bases; for simplicity we denote these as ‘LBCs’.

7 Contra accounts positing that Portuguese Judges made Art. 19 TEU justiciable (Bonelli & Claes, Citation2018; Ovádek, Citation2023), the Court established this LB four years prior in Adhésion de l'Union à la CEDH (2014) at par.163.

8 C-416/10, Križan and Others [2013], ECLI:EU:C:2013:8, at para.65.

9 Both of these new LBCs were leveraged by the Court to justify blocking the EU's accession to the ECHR, which paradoxically, would have expanded the EU's scope of ROL action. Nevertheless, the ruling highlighted the Court's view that the EU treaties have constitutional precedence over international law. See Adhésion de l'Union à la CEDH at par.163.

10 In this article we do not focus on instances where the Commission obstructed ROL enforcement unless this obstruction was aimed at a judicial innovation that had yet to be established by the Court. For instance, if the Commission obstructed a preliminary reference on the basis of Art. 19 TEU after its establishment in the Adhésion de l'Union à la CEDH [2014] judgment, this obstructionism would be ignored.

11 C-64/16, Portuguese Judges [2018] ECLI:EU:C:2018:117, at par.35.

12 C-430/21, RS [2022], ECLI:EU:C:2022:99, at par. 94.

13 C-284/16, Achmea [2018], ECLI:EU:C:2018:158, at par. 60.

14 C-416/17, Commission v France [2018], ECLI:EU:C:2018:811, at par. 115.

15 While the Court's interpretation of Art. 50 TEU differed in the details and requirements surrounding the process of revoking a formal withdrawal notice from the EU, it did not change the Commission's formulation.

16 C-78/18, Commission v Hungary [2020], ECLI:EU:C:2020:476, at par. 145.

17 Infringment referral C-204/21, Commission v Poland lodged April 1st, 2021.

18 C-204/21, Commission v Poland [2023], ECLI:EU:C:2023:442, at par. 389

19 C-64/16, Associação Sindical dos Juízes Portugueses [2018] ECLI:EU:C:2018:117, at pars. 34-38.

20 C-619/18, Commission v. Poland [2019], ECLI:EU:C:2019:531, at pars. 74–77.

21 C-556/17, Torubarov [2019], ECLI:EU:C:2019:626, at pars. 57–58.

22 C-78/18, Commission v. Hungary [2020], ECLI:EU:C:2020:476, at pars. 111–113.

23 C-896/19, Repubblika [2021], ECLI:EU:C:2021:311, at pars. 62–65.

24 C-156/21, Hungary v. Parliament and Council [2022], ECLI:EU:C:2022:97, at pars. 128, 133.

25 Unfortunately, we were unable to review the Commission's interventions in C-156/21 and C-157/21 since they were adjudicated in an expedited procedure, hence the Commission only delivered oral observations.

26 See Opinion of Advocate General Wathelet in C-284/16, Achmea [2018], pars. 39–40.

27 C-556/17, Torubarov [2019], pars. 57–60.

28 C-619/18, Commission v. Poland [2019], ECLI:EU:C:2019:531, pars. 63–64.

29 Opinion of Advocate General Tanchev in C-791/19, Commission v. Poland [2021], at par. 47.

30 C-619/18, Commission v. Poland [2020], par. 19.

31 Report of 22 October 2019, COM(2019) 499 Final and MCV Report of 2019, SWD(2019) 393 Final.

References

- Alter, K. J., & Meunier-Aitsahalia, S. (1994). Judicial politics in the European community. Comparative Political Studies, 26(4), 535–561. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414094026004007

- Arrebola, C., Mauricio, A. J., & Portilla, H. J. (2016). An econometric analysis of the influence of the advocate general on the court of justice of the European union. Cambridge International Law Journal, 5(1), 82–112. https://doi.org/10.4337/cilj

- Baquero Cruz, J. (2018). What's left of the law of integration? Oxford University Press.

- Becker, S., Bauer, M., Connolly, S., & Kassim, H. (2016). The Commission: Boxed in and constrained, but still an engine of integration. West European Politics, 39(5), 1011–1031.

- Bickerton, C. J., Hodson, D., & Puetter, U. (2015). The new intergovernmentalism. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 53(4), 703–722.

- Blauberger, M., Heindlmaier, A., Kramer, D., Martinsen, D. S., J. Sampson Thierry, Schenk, A., & Werner, B. (2018). Ecj judges read the morning paper. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(10), 1422–1441. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1488880

- Blauberger, M., & Sedelmeier, U. (2024). Sanctioning democratic backsliding in the European union, Journal of European Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2024.2318483

- Bonelli, M., & Claes, M. (2018). Judicial serendipity. European Constitutional Law Review, 14(3), 622–643. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1574019618000330

- Brekke, S. A., Fjelstul, J., Hermansen, S., & Naurin, D. (2023). The CJEU Database Platform: Decisions and Decision-Makers. Journal of Law and Courts, 11(2), 389–410. https://doi.org/10.1017/jlc.2022.3

- Burley, A.-M., & Mattli, W. (1993). Europe before the court. International Organization, 47(1), 41–76. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300004707

- Byberg, R. (2017). The history of common market law review 1963–1993. European Law Journal, 23(1–2), 45–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/eulj.2017.23.issue-1-2

- Caporaso, J., & Keeler, J. (1995). The European community and regional integration theory. The State of the European Union (pp. 29–62).

- Closa, C. (2019). The politics of guarding the treaties. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(5), 696–716. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1477822

- Deters, H., & Falkner, G. (2021). Remapping the European agenda-setting landscape. Public Administration, 99(2), 290–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.v99.2

- Dinan, D. (2016). Governance and institutions. Journal of Common Market Studies, 54, 101. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.v54.S1

- Emmons, C., & Pavone, T. (2021). The rhetoric of inaction. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(10), 1611–1629. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1954065

- Falkner, G. (2018). A causal loop? The Commission’s new enforcement approach in the context of non-compliance with EU law even after CJEU judgments. Journal of European Integration, 40(6), 769–784. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2018.1500565

- Fjelstul, J. (2023). Iuropa. R package version 0.1.0.

- Fjelstul, J., & Carrubba, C. (2018). The politics of international oversight. American Political Science Review, 112(3), 429–445. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000096

- Gewirtz, P. (1995). On i know it when i see it. Yale Law Journal, 105, 1023. https://doi.org/10.2307/797245

- Giersch, H. (1985). Eurosclerosis (Technical report). Kieler Diskussionsbeiträge.

- Hernández, G., & Closa, C. (2023). Turning assertive? West European Politics (pp. 1–29).

- Hodson, D. (2013). The little engine that wouldn't. Journal of European Integration, 35(3), 301–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2013.774779

- Hofmann, A. (2013). Strategies of the repeat player [PhD thesis]. Universität zu Köln.

- Hooghe, L. (2001). The European commission and the integration of Europe. Cambridge University Press.

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2009). A postfunctionalist theory of European integration. British Journal of Political Science, 39(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000409

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2019). Grand theories of European integration in the twenty-first century. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(8), 1113–1133. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1569711

- Kelemen, R. D. (2019). Is differentiation possible in rule of law?. Comparative European Politics, 17, 246–260. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-019-00162-9

- Kelemen, R. D. (2023). The European union's failure to address the autocracy crisis. Journal of European Integration, 45(2), 223–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2022.2152447

- Kelemen, R. D. (2024). Will the European union escape its autocracy trap? Journal of European Public Policy, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2024.2314739

- Kelemen, R. D., & Pavone, T. (2023). Where have the guardians gone?. World Politics, 75(4), 779–825. https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.2023.a908775

- Kochenov, D. (2016). Declaratory rule of law. In Self-constitution of European society (pp. 159–180). Routledge.

- Kochenov, D., & Bard, P. (2020). The last soldier standing? courts versus politicians and the rule of law crisis in the new member states of the EU. In E. Hirsch Ballin, M. Stremler, & G. van der Schyff (Eds.), European yearbook of constitutional law 2019 judicial power: Safeguards and limits in a democratic society (Vol. 1, pp. 243–287). The Hague: T.M.C. Asser Press.

- Kochenov, D., & Pech, L. (2016). Better late than never?. Journal of Common Market Studies, 54(5), 1062–1074. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.v54.5

- Krehbiel, J. N., & Cheruvu, S. (2022). Can international courts enhance domestic judicial review?. Journal of Politics, 84(1), 258–275. https://doi.org/10.1086/715250

- Kreppel, A., & Oztas, B. (2017). Leading the band or just playing the tune?. Comparative Political Studies, 50(8), 1118–1150. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414016666839

- Leino-Sandberg, P. (2021). The politics of legal expertise in EU policymaking. Cambridge University Press.

- Leino-Sandberg, P. (2022). Enchantment and critical distance in eu legal scholarship. European Law Open, 1(2), 231–256. https://doi.org/10.1017/elo.2022.17

- Lenaerts, K. (2023). On checks and balances. Columbia Journal of European Law, 29(2), 25–64.

- Lenaerts, K., & Gutiérrez-Fons, J. (2010). The constitutional allocation of powers and general principles of EU law. Common Market Law Review, 47(6), 1629–1669. https://doi.org/10.54648/cola2010069

- Maduro, M. (1998). We the court. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Magyar, B. (2016). Post-communist mafia state. Central European University Press.

- Makszimov, V. (2023). Strategic use of extrajudicial citations at the European court of justice. Working paper on file with authors.

- Mancini, F., & Keeling, D. (1994). Democracy and the European court of justice. Modern Law Review, 57, 175. https://doi.org/10.1111/mlr.1994.57.issue-2

- Matthijs, M. (2023). How Poland's election results could reshape Europe. Council of Foreign Relations.

- Mayoral, J., & Torres Perez, A. (2018). On judicial mobilization. Journal of European Integration, 40(6), 719–736. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2018.1502285

- Meijers Committee (2023). Rule of law dashboard.

- Mérand, F. (2021). The political commissioner. Oxford University Press.

- Moravcsik, A. (2014). Transparency: The revolution in qualitative research. PS: Political Science & Politics, 47(01), 48–53.

- Möschel, M. (2019). How ‘liberal’ democracies attack(ed) judicial independence. In Judicial power in a globalized world. Springer.

- Müller, H. (2019). Political leadership and the European commission presidency. Oxford University Press.

- Nugent, N., & Rhinard, M. (2016). Is the European commission really in decline?. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 54(5), 1199–1215.

- Ovádek, M. (2021). Facilitating access to data on European union laws. Political Research Exchange, 3(1), Article 1870150. https://doi.org/10.1080/2474736X.2020.1870150

- Ovádek, M. (2023). The making of landmark rulings in the European union. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(6), 1119–1141. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2066156

- Palayret, J.-M. (2006). Visions, votes, and vetoes. Peter Lang.

- Pavone, T. (2019). From marx to market. Law & Society Review, 53(3), 851–888. https://doi.org/10.1111/lasr.v53.3

- Pavone, T. (2022). The ghostwriters. Cambridge University Press.

- Pavone, T., & Kelemen, R. D. (2019). The evolving judicial politics of European integration. European Law Journal, 25(4), 352–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/eulj.v25.4

- Pech, L., & Kochenov, D. (2021). Respect for the rule of law in the case law of the European court of justice (Report No. 3, pp. 1–234). SIEPS.

- Pech, L., & Scheppele, K. L. (2017). Illiberalism within. Cambridge Yearbook of European Legal Studies, 19, 3–47. https://doi.org/10.1017/cel.2017.9

- Phelan, W. (2019). Great judgments of the European court of justice. Cambridge University Press.

- Pircher, B. (2023). Compliance with eu law from 1989 to 2018. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 61(3), 763–780.

- Pollack, M. A. (1998). The engines of integration? In European integration and supranational governance. Oxford University Press.

- Priebus, S., & Anders, L. H. (2023). Fundamental change beneath the surface: The supranationalisation of rule of law protection in the European Union, Journal of Common Market Studies, 62(1), 224–241.

- Rasmussen, M. (2014). Revolutionizing European law. International Journal of Constitutional Law, 12(1), 136–163. https://doi.org/10.1093/icon/mou006

- Sadurski, W. (2019). Poland's constitutional breakdown. Oxford University Press.

- Sartori, G. (1970). Concept misformation in comparative politics. American Political Science Review, 64(4), 1033–1053. https://doi.org/10.2307/1958356

- Scheppele, K. L. (2023). The treaties without a guardian. Columbia Journal of European Law, 29, 93.

- Scheppele, K. L., Kochenov, D., & Grabowska-Moroz, B. (2020). Eu values are law, after all. Yearbook of European Law, 39, 3–121. https://doi.org/10.1093/yel/yeaa012

- Scheppele, K. L., & Morijn, J. (2023). What price, rule of law? In The rule of law in the EU. Swedish Institute for European Policy Studies.

- Snyder, F. (1993). The effectiveness of European community law. The Modern Law Review, 56(1), 19–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/mlr.1993.56.issue-1

- Solanke, I. (2011). Stop the ECJ? European Law Journal, 17(6), 764–784. https://doi.org/10.1111/eulj.2011.17.issue-6

- Soyaltin-Colella, D. (2022). The EU's ‘actions-without-sanctions’?. European Politics and Society, 23(1), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/23745118.2020.1842698

- Spieker, L. (2023). EU values before the court of justice. Oxford University Press.

- Stein, E. (1981). Lawyers, judges, and the making of a transnational constitution. American Journal of International Law, 75(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.2307/2201413

- Stone Sweet, A. (2004). The judicial construction of Europe. Oxford University Press.

- Stone Sweet, A. (2010). The European court of justice and the judicialization of eu governance. Living Reviews in EU Governance.

- Stone Sweet, A., & Brunell, T. (2012). The European court of justice, state noncompliance, and the politics of override. American Political Science Review, 106(1), 204–213. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055412000019

- Tallberg, J. (2000). Supranational influence in eu enforcement. Journal of European Public Policy, 7(1), 104–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/135017600343296

- Tallberg, J. (2002). Paths to compliance. International Organization, 56(3), 609–643. https://doi.org/10.1162/002081802760199908

- Tömmel, I., & Verdun, A. (2017). Political leadership in the European union. Journal of European Integration, 39(2), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2016.1277714

- Tridimas, T. (1997). The role of the advocate general in the development of community law. Common Market Law Review, 34(6), 1349–1387. https://doi.org/10.54648/157630.

- Tridimas, T. (2014). Fundamental rights, general principles of eu law, and the charter. Cambridge Yearbook of European Legal Studies, 16, 361–392. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1528887000002676

- Van Elsuwege, P., & Gremmelprez, F. (2020). Protecting the rule of law in the eu legal order. European Constitutional Law Review, 16(1), 8–32. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1574019620000085

- Vauchez, A. (2010). The transnational politics of judicialization. European Law Journal, 16(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/eulj.2010.16.issue-1

- Vauchez, A. (2017). Eu law classics in the making. In EU law stories. Cambridge University Press.

- Vissers, N. (2023). Enforcing democracy. Verfassungsblog.

- Von Bogdandy, A. (2010). Founding principles of eu law. European Law Journal, 16(2), 95–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/eulj.2010.16.issue-2

- Von Bogdandy, A., Bogdanowicz, P., Canor, I., & Taborowski, M. (2018). A potential constitutional movement for the European rule of law.

- Weiler, J. H. (1991). The transformation of Europe. Yale Law Journal, 100(8), 2403–2483. https://doi.org/10.2307/796898

- Weiler, J. H. (1994). A quiet revolution. Comparative Political Studies, 26(4), 510–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414094026004006

- Winzen, T. (2023). How backsliding governments keep the European union hospitable for autocracy. The Review of International Organizations, 1–30.