ABSTRACT

This paper presents an innovative narrative data analysis approach, used in a narrative research project exploring student values. The work of three different authors was drawn upon to create a novel, rigorous and synergistic analysis tool. A novel approach to data analysis, using the stories told by one Generation Z (Gen Z) student and the personal values elicited, which are drawn from Schwartz’s theory of universals in basic human values is presented. This leads to a restorying of the data, from which the reader finds meaning. The participant was interviewed at the beginning of their first year as undergraduate and is presented as an example from the larger study of seven Gen Z students. How this approach is effective is examined, demonstrating that combining theory and the narrative analysis approach enabled the values of self-direction, security, benevolence and power to be exposed within the resulting restorying. This is a new and innovative approach to narrative analysis that can be applied in a wide range of contexts internationally and utilised in future studies.

Introduction

University students begin their undergraduate journey with a story. A story, or narrative, that tells of what has happened and mattered during the lead up to starting at university. This paper considers the story told by students and the personal values elicited, in relation to Schwartz’s theory of universals in basic human values (Schwartz et al. Citation2012, Schwartz and Bilsky Citation1987). Using narrative inquiry as methodology, this study focuses on the year before starting at university. To gather this data, online short-story narrative interviews were conducted with Generation Z students (those born between 1995 and 2012) in their first semester. In order to analyse the data effectively, a bespoke approach to analysis was developed, combining the work of three authors (Leggo Citation2008, Loseke Citation2009, Phoenix Citation2017) so that the data were sifted, questions posed to go deeper, and finally key terms identified and used to unpack the meaning within the stories. In order to enable rigour in data analysis, whilst retaining the distinct stories of each participant, the three-staged approach was used in preference to more traditional methods. The approach has been applied to several student stories, but this paper will illustrate the triad approach by exploring the story of one Gen Z student, to create a restoried piece illustrating their values. The innovative approach to synthesising theory has the potential to impact future studies by providing a novel and multi-layered model of data analysis.

Context and rationale

Higher education (HE) has changed in the latter part of the twentieth century due to massification and globalisation, meaning that in the United Kingdom (UK) today, participation exceeds 50% (Scott Citation2021, Tight Citation2019). Working in HE today is a dichotomy; it is a metrics-driven environment, whilst at the same time focusing on student experience (Tight Citation2018). Educators face additional new challenges with the arrival of students from Gen Z at university campuses. Gen Z is the largest proportion of the current and future undergraduate student group (with Gen Z defined as born between 1995 and 2012). This generation of students influences the ethos of universities with Duffy (Citation2021) recognising challenges at this time as a result of the 2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. Duffy (Citation2021) highlights that ‘over a fifth of the latest generation of young people (22%) are starting out adult life with signs of a common mental health disorder, compared with 15% of Millennials back in 1998, when they were the same average age’ (99). Duffy reports on research conducted across 30 countries to find the top and bottom five characteristics for each generation through the Ipsos Global trends survey (2019). The responses by the public in this survey about Gen Z are very negative. Whilst acknowledging Gen Z as ‘tech savvy’, the Ipsos survey shows that Gen Z are also viewed by people as lazy, arrogant, selfish and materialistic. Duffy (Citation2021) notes from these findings that negative stereotypes about youth are common from one generation to the next. Earlier North American studies (Seemiller and Grace Citation2016; Seemiller and Grace Citation2017, fundamental convictions, ideals, standards or life stances which act as general guides to behaviour or as points of reference in decision-making or the evaluation of beliefs or action’ by Halstead (Citation1996, p.5)) explore the nuances and identifying factors of these emerging adults (Appleman Citation2015, Arnett Citation2000). Gen Z students are digitally surrounded, with Zorn (Citation2017) arguing that they have ‘one continuous online, computer-connected experience’ (61). Seemiller and Grace Citation2016, Citation2017) identify what matters to this group through a survey of more than 750 students from 15 institutions in the United States of America (USA), with additional material taken from other sources such as market research and polling data. Happiness, relationships, financial security and stability, meaningful work and helping others are seen as key factors that matter to this group. Gen Z are characterised as being relationally motivated to make a difference and not let others down. Values of open-mindedness, caring and diversity are also evident in Seemiller and Grace’s (Citation2016, Citation2017). However, the work relates to American Gen Z students and refers to college life. The reporting has a very positive presentation, which needs to be explored in a non-US context. This paper explores an example of the data from the first author’s study on experiences and personal values of Generation Z students from an English university utilising narrative inquiry.

Defining values

Values can be referred to as principles, fundamental convictions, ideals, standards or life stances which act as general guides to behaviour or as points of reference in decision-making or the evaluation of beliefs or action’ by Halstead (Citation1996, p.5). Contextually, as environmental influences (such as being in HE) may affect value formation, therefore this study explores the values of students in a context, higher education. It highlights the role of the environmental components of personal values (Schermer et al. Citation2011). Schwartz’s (Citation1992), Schwartz et al. (Citation2012 notable theory of universal values establishes domains of values, or groups that embody the same value type, rather than single values. This is exemplified by the 10 values in the diagram below ():

Schwartz’s 10 values have been widely accepted by academics in the field (Schwartz and Bardi Citation2001, Ryckman and Houston Citation2003, Davidov et al. Citation2011).

Materials and Methods

Narrative inquiry

Narrative inquiry, the study of experience as story, is primarily a way of thinking about experience. Considered a relatively new approach, in narrative inquiry there is an acknowledged and subjective studying of people (Bruce et al. Citation2016). It is a relational methodology, with researchers hearing about ordinary lived experience and privileging it as unique and worth listening to for itself (Clandinin and Rosiek Citation2007).

Capturing stories of what matters to students (using Narrative Inquiry) is a research opportunity in the field of values. Prominent narrative research authors state that people’s lives are storied, and this study follows this premise (Clandinin and Connelly Citation2000; Savin Baden and Howell-Major Citation2013). Applying social constructivist theory and Dewey’s (Citation1997) theory of experience, narrative research allows students’ stories of experiences to be listened to and analysed. The importance of this is asserted by Leggo (Citation2008), who explains: ‘[W]hat writers, storytellers, and artists of all kinds do is frame fragments of experience, in order to remind us that there is significance in the moment, in the particular, and in the mundane’ (5).

Narrative interviews

Kvale and Brinkmann (Citation2009) identify that there are three types of narrative interview: the short story, the life story and oral history. Kvale and Brinkmann (Citation2009) define narrative short story interviews (NSSI) as about specific episodes of time, with life story interviews asking for the perspective of the interviewee on their life, and oral history interviews considering the community history beyond the individual. NSSI was chosen for this study to capture the interviewees responses to the complexities of the research question, taking into account-specific episodes of time, or life episodes (Palaiologou, Needham, and Male Citation2016). In addition to Kvale and Brinkmann’s three interview forms, Clandinin and Connelly (Citation2000) and Clandinin (Citation2013) use the terms annals and chronicles, a way to order and shape the narratives. Participants construct timelines beginning at a significant date. Annals are memories and dates from within the timeline, and chronicles are then what happens around that timeframe as a series of events (Clandinin and Connelly Citation2000). Here, students as participants were asked to share their experiences about the period before starting university.

Narrative interviews seek to understand individual experience (Gaudet and Robert Citation2018). The NSSI method of narrative interviewing focuses on what the interviewee’s experience has been, acknowledging that the interviewee is on a journey (Brinkmann Citation2017). Arguably, the narrative interview is a distinctive space for listening to the experiences of the interviewees, so thick description can be achieved to ensure the trustworthiness and transferability of the research findings (Armstrong Citation2012, Flynn and Black Citation2013, Lincoln and Guba Citation1985, Citation1986).

A major advantage of narrative interviews is that they ‘place the people being interviewed at the heart of a research study’ (Anderson and Kirkpatrick Citation2016, 631). This means that narrative interviews help understanding others’ behaviours and experiences, seeking answers about a participant’s life (Josselson Citation2007). The interview can focus on certain topics, events or experiences (Elliott Citation2005) and the research design has a nondirective approach. Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill (Citation2019) explain this subtlety as starting with a general, opening question, followed by prompts. Within the boundaries of the short story narrative time frame, described above, the interviewer then asks for the participant to relate their story, in annals and chronicles, telling their memories of a certain time. Prompts are improvised (Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill Citation2019). The phenomenon being studied is not disclosed directly, rather the participant tells the interviewer about their life (Josselson Citation2007).

When a participant tells an aspect of their story spontaneously, it could turn out to be of interest to the interviewer (Czarniawska Citation2004). These aspects of the story provide insights into the world of the participant and make interviewing exciting for the interviewer (Kvale and Brinkmann Citation2009). Several authors have used narrative interviews to explore the lived experience of students from middle school to HE (Clandinin and Connelly Citation2000, Goodson et al. Citation2010, Holton and Riley Citation2014). Clandinin and Connelly (Citation2000) utilised detailed life stories as a way to look at student experience in a middle school. Goodson et al. (Citation2010, 3) applied the life story narrative interview to gain an understanding of lifelong learning in HE; and Holton and Riley (Citation2014) considered the lived experiences of HE students in their understanding of the cities they lived in, using walking interviews to elicit short stories from this time. All these studies, as with the one reported here, mirrored my intentions through investigating rich narratives of the topic investigated. This study used NSSI because it is an appropriately nondirective interview method to elicit deeper insights into students’ values at specified times during their undergraduate degree.

The interview process: recruitment

As the intention of the study was to hear stories and gather rich, qualitative data, eight participants were sought. At the time of the research due to COVID-19, England was in its third lockdown, with universities mandated to teach online, except where courses required specialist input. An email invitation to participate was sent to potential student participants, via Department Administrators. The students were in the first year of undergraduate study across courses in Academic Studies in Education. From this call, initial responses came from ten students. Subsequently, three of the students were removed because they were outside of the Gen Z age range. The seven participants met the inclusion criteria and Microsoft Teams interviews were scheduled.

Following a successful pilot exercise to ascertain the preferred question approach, communication via email was undertaken to establish rapport and break the ice prior to the interview, acknowledging that building relationships is critical in narrative research (Josselson Citation2007). This follows the relational approach of narrative inquiry and the concept of space and place (Clandinin and Connelly Citation2000). The welcoming email was followed by an email the day before the interview, asking the participant to think about the short stories they might want to tell in response to the introductory questions noted below:

What is the beginning of your story of that time (when you decided you were coming to university)?

What reasons helped you decide to come to university?

Who was significant in your decision and why?

Did anything change during the time before you came to university and how did that make you feel?

Just before you began university, what were the things that mattered to you about being a student?

The interview

It was important to listen and respond carefully during the narrative interviews (Clandinin and Connelly Citation2000). It was also important to not interrupt (Mishler Citation1986). However, Josselson (Citation2007) contends that it is possible that some stories may be emotional as the participant shares their stories and explores the research area, and therefore, an appropriate response was rehearsed to illustrate understanding and empathy in the online space (Iacono, Symonds, and Brown Citation2016).

After welcoming the participants on Microsoft Teams at the agreed time, there were a few moments of conversation to develop the relationship and settle the interviewee. I (Lead Author) chose to wear my LGBTQ+ Allies lanyard to demonstrate my inclusive-self and I wore a plain t-shirt to try and denote a less formal approach to my position as lecturer. The intention was to diminish the power imbalance and develop social interaction, a challenge of interviews (Clandinin and Connelly Citation2000, Cresswell and Poth Citation2018, Kvale and Brinkmann Citation2009, Lincoln and Guba Citation1985). The participants, as they narrated their short stories in response to the first question and prompts, took themselves back to the year before they commenced university, locating themselves in that time (Clandinin and Connelly Citation2000, Daiute and Cynthia Citation2004).

All participants referred to the questions they had received by email and used them to guide themselves through the interview. Occasionally, they required gentle prompting to move to the next question. Once they had finished narrating, a short break was taken as online interviewing can be intense (Morgan Citation2020). Narrative interviews need time for the participant to share their stories, and they can range from half an hour to several hours (Anderson and Kirkpatrick Citation2016). The reported interview below lasted 50 minutes. Follow-on prompts or secondary questions enabled the participant to develop the characters spoken about in their stories and to expand upon the episodes shared (Goodson Citation2013, Kvale and Brinkmann Citation2009). As such, the stories told moved inwards and outwards and backwards and forwards (Clandinin and Connelly Citation2000), as participants reflected back on the year before they came to university.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for this study was given by the University Research Ethics Panel. Beyond this procedural necessity, it was necessary to consider ethics throughout the research process, from its conception to its conclusion (Clandinin and Rosiek Citation2007) and to consider the ethics of the researcher in the role – from the research design and making sure the questions asked are ethical, to having an ethical strategy for sampling, to conducting an interview in an ethical way, to transcribing and reporting ethically (Kvale and Brinkmann Citation2009; Dhillon and Thomas Citation2019). As a professional in the institution, prior knowledge and experience of working with students mitigated for ‘othering’, as I knew the population well having worked in HE for over a decade. Having a prior understanding of the participant group in my role as lecturer enabled an emerging understanding of them and care for them (Caine, Clandinin, and Lessard Citation2022).

Being a member of staff was an additional consideration in this project and could have brought ethical issues and dilemmas (Dhillon and Thomas Citation2019). To mitigate this, data collection points were planned to ensure direct teaching of the participants was not taking place and conversations with a peer debriefer enabled reflection on this dichotomy of being an insider yet outsider.

Sensitivity and anonymity were therefore important and participants chose their own pseudonym to support anonymity (Goodson et al. Citation2010). However, as an insider-researcher who works in the university in which the participants study, I also recognised that anonymising the institution was challenging (Floyd and Arthur Citation2012). This furthered my intent to take ‘relational responsibility’ (Floyd and Arthur Citation2012, 176) and conduct the research with an ethics of care, from the interview to the data analysis.

Data analysis

Narrative analysis is shaped by questions of meaning and social significance (Clandinin and Connelly Citation2000). It investigates the story, asking: how is it organised? Why was it told this way? (Reissman Citation1993). Bruce et al. (Citation2016) illustrate narrative analysis as considering storylines rather than themes because they reflect better the words of the participants, weaving in and out of time, shifting and involving multiple patterns. In addition, Gaudet and Robert (Citation2018) discuss examining the organisation of the individual’s narrative because values can be revealed through interviews. This relates to Feldman and Almquist’s (Citation2012) work which analyses the implicit in stories and emphasises that through narrative values can be conveyed.

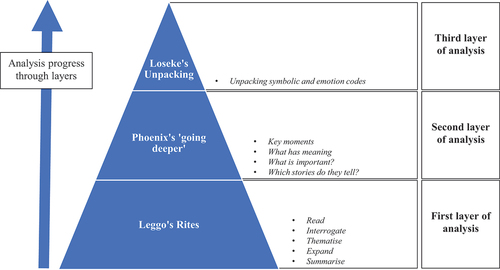

A distinction of narrative analysis is that each interview is individually analysed for the lived experience, in all its layered and textured self, rather than seeking themes or broad concepts across the data set (Chase Citation2018, Etherington Citation2004, Reissman Citation1993). The way data are analysed and the inductive process undertaken means that patterns are identified, consistencies are seen and meanings uncovered (Gray Citation2013). Numerous authors have documented their approaches illustrating the range of narrative analysis available (Crossley Citation2000, Leggo Citation2008, Loseke Citation2012, Reissman Citation1993, Safford and Safford Citation1930). In fact, a number of authors (Reissman Citation1993, Cresswell Citation2007, Bold Citation2012, Cresswell and Poth Citation2018) comment on the different approaches that can be employed, outlining the challenge when selecting an appropriate analysis approach to use. For this study, a single narrative analysis approach did not meet the needs of the data or the research question, because although analysing for values, participants were not asked to state their values, instead they were carefully inferred through the stories they told. The work of three different authors (Leggo Citation2008, Loseke Citation2009, Phoenix Citation2017) was drawn upon to create a rigorous and synergistic analysis tool. The diagram below () illustrates the layers of analysis. The first layer using Leggo’s RITES (Leggo Citation2008) is an initial sift of the data; going deeper with the second layer of analysis, focusing on precision (Phoenix Citation2013, Citation2013, Citation2017); and finishing with the third layer of analysis – unpacking symbolic and emotion codes (Loseke Citation2009, Citation2012) to consider the more abstract meaning in the data. The analysis at each of these layers is outlined in .

Figure 2. Triad of narrative analysis from sifting to precision, to the abstract (created from the three previous approaches).

Reissman (Citation1993) suggests that the analytical approach should be coherent and visible so that the movement from raw data to analysis is explicit. Thus, the triadic approach illustrated responds to her statement, to provide coherence, visibility, and rigour (Lincoln and Guba Citation1985). In this study, analysis was initially by hand and on paper, subsequently presented as a table (see ).

Table 1. Leggo’s RITES (Leggo Citation2008, 6–7).

Table 2. First layer analysis using Leggo’s, Citation2008.

Table 3. Second layer analysis using Phoenix’s questions (2013, Phoenix Citation2017.).

Table 4. Showing third layer analysis using Loseke’s symbolic and emotion codes (2009).

First layer of analysis- Leggo’s RITES

Leggo’s Citation2008 was chosen as it is very straight forward. Leggo (Citation2008) considers this a simplistic tool to start narrative analysis. It follows five steps ():

The second step, interrogate, involves extracting words and phrases from the transcript in different colours that related to each of the questions (who? what? where? when? why? how? so what?). This interrogation enabled answering of the initial question from Reissman (Citation1993): how was it organised?

Interrogation allowed for reordering of the narrative, so that episodes recounted could be connected to other episodes in the same interview where relevant. As this was a NSSI (Kvale and Brinkmann Citation2009) with defining boundaries of the year before coming to university (September 2019 to September 2020), analysing the data for ‘when’ allowed a chronological re-presentation. This chronological ordering of the story allowed for clarity even where the participant had moved in and out of episodes during their narrative (Clandinin and Connelly Citation2000).

Steps three and four, thematise and expand, involve reading the transcript whilst looking for the meaning that the participants had implied either overtly or through the behaviour they described. To aid this process, Schwartz’s values theory (Citation2006), drawn as a diagram with related behaviours linked to the core values, was used to infer values from the narrative (see Appendix A). The values were recorded in a table. This first shift of the data is demonstrated in .

Second layer of analysis- Phoenix’s going deeper

The second layer of narrative analysis used the work of Ann Phoenix, an experienced narrative researcher in the field of ‘psychosocial, including motherhood, social identities, young people, racialisation and gender’ (Phoenix Citation2021). Phoenix (Citation2013, Citation2017) recommends asking deeper questions of the narrative, which became subheadings on the analytical page: what are the key moments? what has meaning or what has importance? and which stories are told? These questions were drawn from Phoenix’s work and when the process of analysis began, it was clear that the questions about meaning and importance were connected. Therefore, in this study, they became one question. The third subheading- which stories are told? - began to organise the narrative into clear episodes. Phoenix’s questions gave clarity for the structure of the restorying (see next section).

This process was first recorded on paper then transferred onto the next column of the analysis table ().

Phoenix’s questions related to the aim of this study and allowed for extraction of themes relevant to the research question (). They also linked to Reissman’s (Citation1993) overarching second question: why was it told this way? Phoenix was appropriate for the second layer of analysis because of the precision of her questioning and the clarity of her approach.

Third layer of analysis- Loseke’s unpacking

Further interpretation of the raw data came through the final layer of analysis, a specific focus on words and phrases used by the participant. Loseke has undertaken narrative analysis of the choices made with language (Kusenbach and Loseke Citation2013; Loseke Citation2007, 2009, Citation2012), specifically symbolic language choice and emotional language choices. She refers to these as symbolic codes and emotion codes. Symbolic codes are the commonly held and understood expressions used in narratives of identity, recognised in stories as well-known terms such as the good/bad mother (Loseke Citation2012). Emotion codes relate to how one feels when reading a text, referred to as ‘cultural ways of feeling’ by Loseke (Citation2009, 498). Although subjective and interpretive, both symbolic and emotion codes seemed appropriate to use to support the technique of restorying the participant’s narratives, so that meaning and voices could be unpacked from the narrative. Emotion codes ‘are sets of socially circulating ideas about which emotions are appropriate to feel when, where, and towards whom or what, as well as how emotions should be outwardly expressed’ (Loseke Citation2009, 497). In my interpretation, emotion codes are about using the external to understand the internal.

Symbolic codes occur in all stories individuals narrate and are connected to emotion codes (Loseke Citation2012). Distinctively, I established that symbolic codes can be used to connect Jungian archetypes in the analysis as they signify systems of ideas or meanings. Meanwhile, emotional codes inform values and appropriate behaviours (Loseke Citation2009). As Loseke explains: ‘The contents of symbolic and emotion codes are not fixed or agreed upon’ (2009, 501) and therefore they are interpretive and semiotic, whereby signs and symbols used in stories denote meaning. In practice, this involved further re-reading the transcript for words and phrases that could be identified as emotional, or symbolic, interpreting more abstract words and phrases from the data (see , below).

Loseke (Citation2012) reiterates the point, made by Reissman (Citation1993) and Cresswell and Poth (Citation2018), that analysing narratives can be a challenging and contested field, and she recommends using a range of strategies. This further supports the development of this triad approach. This three-layered approach to analysis enable holistic analysis (Elliott Citation2005) and this fitted appropriately with the aims of the research undertaken. The analysis of each individual participant’s story involved a lengthy and systematic approach that was rigorous and responsive to the research aims. The triadic, bespoke analysis strategy enabled meaning making appropriate to the study. Ultimately, this resulted in efficacious data tables (as presented) for each participant, including all important data.

Results

Restorying

After the analysis and interpretation undertaken using the triadic analysis, the final stage involved creating a coherent restorying (Cresswell and Poth Citation2018, Crossley Citation2000). The restorying is told by the researcher about the experiences of the participant and has a beginning, middle and end (Connelly and Clandinin Citation1990, Ollerenshaw and Creswell Citation2002). Ollerenshaw and Creswell (Citation2002, 332) explain how to represent meaning and sequence the narrative using a restorying approach:

Restorying is the process of gathering stories, analysing them for key elements of the story (e.g., time, place, plot, and scene), and then rewriting the story to place it within a chronological sequence. Often when individuals tell a story, this sequence may be missing or not logically developed, and by restorying, the researcher provides a causal link among ideas. In the restorying of the participant’s story and the telling of the themes, the narrative researcher includes rich detail about the setting or context of the participants experiences. (Ollerenshaw and Creswell Citation2002, 332)

These restoryings pay homage to the experiences described by the participants, and the questions the researcher has repeatedly asked of the data (Jean and Vera Citation2012). Kvale and Brinkmann (Citation2009, 286). Connelly and Clandinin (Citation1990) refer to restorying as giving voice to the participants. They say that restorying happens when the voices of both the participant and the interviewer are heard, and new meaning is made:

Narrative inquiry is, however, a process of collaboration involving mutual storytelling and restorying as the research proceeds. In the process of beginning to live the shared story of narrative inquiry, the researcher needs to be aware of constructing a relationship in which both voices are heard. (Connelly and Clandinin Citation1990, 4)

Although the interview had focused on the year before university, some participants felt it was relevant to refer to times before this to provide a context and therefore the start point was sometimes before September 2019. The middle of their stories often related to spring 2020 and the COVID-19 outbreak, and the end was the commencement of their university journey in September 2020. Cresswell and Poth (Citation2018) and Nasheeda et al. (Citation2019) explain the process as involving the researcher taking the transcript and imposing chronological sequence (akin to chapters) to the transcript by restorying into a framework that makes sense. Therefore, the restorying framework enabled movement of the transcripts into a sequence with a beginning, middle and end, referring to Connelly and Jean Clandinin’s (Citation1990) concept of time, place and scene. A key aspect of the restorying process is the researcher deciding upon what form of written presentation to use. Crossley (Citation2000) speaks of the author’s lens influencing the restorying, while Connelly and Clandinin (Citation1990) write of three ways of restorying narratives: broadening or generalising; burrowing by concentrating on the events and associated feelings; and exploring the meaning of the story. In this study, a combination of burrowing and exploring was used. Each individual restorying began with a short biography of the participant to provide context. This approach is used by Connelly and Clandinin (Citation1990, 11), who suggest a ‘narrative sketch’ (11) at the beginning of the restorying. Kvale and Brinkmann (Citation2009) advocate that restorying occurs in the head, during the interview itself. Significantly, restoryings are a distinctly different approach used in narrative analysis. The approach is summarised by Reissman (Citation2008, 57): ‘The investigator works with a single interview at a time, isolating and ordering relevant episodes into a chronological biographical account’ (2008, 57). Connelly and Clandinin note that this individualised approach is a ‘challenging task’, but ‘when done properly, one does not feel lost in minutia but always has a sense of the whole’ (1990, p. 7). Inevitably this means that the individual and unique voices are reified through the restorying technique (Clandinin and Connelly Citation2000, Czarniawska Citation2004, Lincoln, Lynham, and Guba Citation2018, Mishler Citation1986, Reissman Citation1993). Arguably then, it is this synergy of the authorial voice of the narrative researcher and the authentic voice of the student participant that results in a readable text that works to address the research question of the study.

An excerpt of Tanya’s restorying

In this section, two episodes from the restoryings of Tanya are presented. These episodes are used to highlight the personal values demonstrated and the behaviours that are spoken of.

An interview was conducted with ‘Tanya’ in December 2020. She is an undergraduate student undertaking a full-time degree in Education Studies and Sociology. She is 24 years old, and this is the second time she has attended university, leaving the first course, working in a range of jobs, and subsequently having a child who is now two years old. Tanya’s stories about the year before she began on her current course at university reveal her personal values and conviction about what matters to her.

The major life event in Tanya’s story at this time is the birth of her son, followed by realising he might have craniosynostosis (a condition when the baby does not have a soft spot, and the skull fuses and does not grow as the brain grows). Strong values of social power are demonstrated by her commitment to follow the feeling that something was wrong, even though medical staff were saying that the baby just had an unusual head shape. Her son was finally diagnosed after Tanya managed to get him seen by Birmingham Children’s Hospital, using her social power and agency. This preservation of closest family resonates with the value of benevolence and security of family and health:

When he was eight weeks old (we were) pretty much back and forth with the hospital because he didn’t have a soft spot and it was something I noticed early on but we were, were always told by the people we saw that it’s fine-he’s just got a funny head shape, but I just had this feeling in me that there was something wrong. So we kept pushing it and eventually we got seen by Birmingham Children’s Hospital, who said they think it might be a condition called craniosynostosis, which is when the skull fuses. (Tanya, Interview 1, December 2020)

Whilst this critical incident has personal impact for Tanya as a mother, her workplace is not sympathetic to her requiring four months extra leave to care for her baby after his operation. Coincidentally, the operation was scheduled on the same day she was supposed to return to work after maternity leave. Tanya notes that she did not really like the company, or the manager, whose comments were somewhat inappropriate in a lot of situations. They told her that she would not be there much longer if she did not return. The value of benevolence is strong, with loyalty of the company criticised, alongside the lack of responsibility and respect from the manager.

Being in the hospital for the seven-hour operation and a long time after that, gave Tanya a lot of time to think. The story identifies a turning point of great consequence for her and her family that comes to light during that emotional and important day. Tanya explains that she always felt unsettled dropping out of her hospitality and events management course, even though she really did not enjoy it. After many different jobs before the birth of her son, this was the first time she was able to think about herself:

I had a lot of time to think then, about what I’m going to do now. Like, obviously because I didn’t have my job anymore. Um, so that was when I kind of thought, ‘I’m going to wait for him to recover and then I’m going to look at going back into work.’ But for me it felt like the first opportunity I’d had to actually go back into uni, because I wasn’t in a job that I felt like ‘Oh, I’ll quit and go to uni.’ I was just like, jobless, so it felt like I have the time to start. (Tanya, Interview 1, December 2020)

The decision can be interpreted as an epiphany, illustrating the values of independence and agency. Tanya’s narrative of this time shows her belief in herself. The alignment of responsibility and self-direction create the agency for change resulting in the subsequent application to university.

Discussion

Evaluation of the restorying and the data analysis approach

In this excerpt from Tanya’s interview, a transformative event occurs, the health issue and subsequent operation on her baby son. As a result of this event, she has an epiphany and decides to return to higher education. Tanya’s values were evident from the interview after the triad analysis approach was applied to the data. Social power and agency, benevolence, family health and security, independence, individual agency, responsibility, and self-direction were all extracted and interpreted from her transcript. For example, Tanya explains that whilst waiting for her son’s lengthy operation to end, she thinks for the first time about herself, about what she wants for her future. Relating these to Schwartz’s theory, the values relate to the fundamental personal values of self-direction, security, benevolence, and power. The data analysis approach enabled a restorying of the interview data into a rounded, readable narrative. The restoried account was sent to Tanya to check or change, if required.

Telling her story in this way envelopes the three parts of the triad approach of analysis and allows the essence of her story to shine through. Reading the restorying, one can feel Tanya’s emotions, and begin to understand her motivation for applying to university at that point. While she presents herself as a worried mother, pursuing meaningful study is also of great importance to Tanya. At the point of writing, Tanya has just submitted her final assignments for her undergraduate degree. She achieved her goal.

Limitations

It is important to recognise some of the limitations or considerations of this approach. Palaiologou, Needham, and Male (Citation2016) stress that it is important to recognise ones’ own bias as the researcher during interpretation. Analysing and representing data as a restoried piece which only echoes the author’s position would show bias. Thus, as well as member checks for credibility (Lincoln and Guba Citation1985, 1986), Clandinin and Connelly (Citation2000) refer to plausibility, and write: ‘A plausible account is one that tends to ring true. It is an account of which one might say “I can see that happening”’ (2000, 8). Here the researcher, the participant and the reader should read the restorying as seemingly true or sincere.

Conclusion

Whilst Tanya is an example of a student from her generation, who experienced similar historical occurrences in her life, she has her own story to tell (Daiute and Cynthia Citation2004). The creation of the bespoke triad analysis approach has enabled a thorough, authentic analysis of the story told. It enabled layered and deeper extraction from the transcript so that Tanya’s story could be made audible. These data are rich and personal, and deserving of an in-depth exploration before being recast in a restoried form for the reader. It was important to give voice to students as participants through narrative inquiry, and to co-construct the final presentation of data. Reflecting on my worldview, this commitment rests well with my (first author) own values, and the desired potential for change as a result, summarised by Mertens (Citation2019, 37) who states: ‘The final written report … includes the voices of participants, the reflexivity of the researcher, and a complex description and interpretation of the problem, and it extends the literature or signals a call for action’. This complexity and richness comes from the social construction of culture and language, whereby multiple meanings and interpretations are elicited (Gray Citation2013, Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill Citation2019). The challenge to share the stories acquired through narrative inquiry can be overcome through this bespoke analysis approach that sifts, goes deeper, and unpacks the emotional and social codes of the stories told. The final restoried piece then can be shared as a reflection of the participant’s story. In this study, that means sharing their values from the year before they started university. As a result, as university staff, we can know our Gen Z students better through this understanding and be better prepared to support and educate them as they join us on campus for their undergraduate journey.

The bespoke triad analysis approach could be applied to a range of narratives to provide a thorough, extensive analysis of the data. Combining the approach with theory (here Schwartz’s values theory) will retain the rigour and focus of the analysis. It is then for the reader to find meaning in the restorying presented.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participant of this research study, known by the pseudonym Tanya.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ellie Hill

Ellie Hill is a Senior Lecturer in the Department for Education and Inclusion at the University of Worcester. She has taught there for nine years, currently teaching on the BA Education Studies degree and MA in Education. Ellie’s professional and research interests are values in education and student voice. From her previous career as a Primary School head teacher, Ellie has been fortunate to follow her passions through to her career in Higher Education. Ellie is currently studying for her doctorate at the University of Worcester. She is exploring the stories of students’ values development during their undergraduate degree. Specifically, Ellie’s participants are members of ‘Generation Z’. Using Narrative Inquiry as methodology, she is seeking to tell the stories of what matters to Gen Z students in HE.

Peter Gossman

Peter Gossman has worked in a range of FE and HE institutions in the UK and NZ in both Education and Academic Development roles. He has worked on a large NZ project investigating the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning as well as publishing, in a range of academic journals, on a variety of subjects, particularly in relation to ‘good’ teaching and conceptions of teaching.

Richard Woolley

Richard Woolley is Professor and Head of the School of Education. He joined the University of Hull in November 2021, having worked previously at the University of Worcester as Head of Centre for Education and Inclusion, Deputy Head of the School of Education and Professor of Education and Inclusion. His career started in primary education in North Yorkshire, before moving to work in further and higher education in Derbyshire and then returning to primary school teaching in Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire. He has served as deputy headteacher and special educational needs coordinator, as well as being curriculum coordinator for several subjects across the primary phase of education. He worked in primary initial teacher education at Bishop Grosseteste University from 2003 to 2011.

References

- Anderson, C., and S. Kirkpatrick. 2016. “Narrative Interviewing.” International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy 38 (3): 631–634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-015-0222-0.

- Appleman, M. 2015. “Emerging Adulthood: The Pursuit of Higher Education.“ Master’s thesis, University of Akron. http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=akron1429111444.

- Armstrong, J. 2012. “Naturalistic Inquiry.” In Encyclopedia of Research Design, edited by N. Salkind, 880–885. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Arnett, J. J. 2000. “Emerging Adulthood: A Theory of Development from the Late Teens Through the Twenties.” American Psychologist 55 (5): 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469.

- Bold, C. 2012. Using Narrative in Research. London: Sage.

- Brinkmann, S. 2017. “The Interview.” In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln, 576–600. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Bruce, A., R. Beuthin, L. Sheilds, A. Molzahn, and K. Schick-Makaroff. 2016. “Narrative Research Evolving: Evolving Through Narrative Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 15 (1): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406916659292.

- Caine, V., Clandinin, D.J., Lessard, S. 2022 Narrative Inquiry: Philosophical Roots (London: Bloomsbury Academic)

- Chase, S. 2018. “Narrative Inquiry: Toward Theoretical and Methodological Maturity.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln, 546–561. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Clandinin, D. J. 2013. Engaging in Narrative Inquiry. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Clandinin, D. J., and F. M. Connelly. 2000. Narrative Inquiry : Experience and Story in Qualitative Research. San Fransisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Clandinin, D. J., and J. Rosiek. 2007. “Mapping a Landscape of Narrative Inquiry: Borderland Spaces and Tensions.” In Handbook of Narrative Inquiry: Mapping a Methodology, edited by D. J. Clandinin, 35–76. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Connelly, F. M., and D. J. Clandinin. 1990. “Stories of Experience and Narrative Inquiry.” Educational Researcher 19 (5): 2–14. https://doi.org/10.2307/1176100.

- Connelly, F. M., and D. Jean Clandinin. 1990. “Stories of Experience and Narrative Inquiry.” Educational Researcher 19 (5): 2–14. https://doi.org/10.2307/1176100.

- Cresswell, J. W. 2007. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Cresswell, J. W., and C. N. Poth. 2018. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Crossley, M. 2000. Introducing Narrative Psychology: Self, Trauma and the Construction of Meaning. Buckingham: Oxford University Press.

- Czarniawska, B. 2004. Narratives in Social Science Research. London: Sage.

- Daiute, C., and L. Cynthia. 2004. Narrative Analysis. Studying the Development of Individuals in Society, edited by C. Dauite and C. Lightfoot. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Davidov, E., G. Datler, P. Schmidt, and S. H. Schwartz. 2011. “Testing the invariance of values in the Benelux countries with the European Social Survey: Accounting for ordinality.” In Cross-cultural analysis: Methods and applications, edited by E. Davidov, P. Schmidt, and J. Billiet, 149–171, Routledge: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Dewey, J. 1997. Experience and Education. New York: Touchstone.

- Dhillon, J. K., and N. Thomas. 2019. “Ethics of Engagement and Insider-Outsider Perspectives: Issues and Dilemmas in Cross-Cultural Interpretation.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 42 (4): 442–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2018.1533939.

- Duffy, B. 2021. Generations: Does When You’re Born Shape Who You Are?. London: Atlantic Books.

- Elliott, J. 2005. Using Narrative in Social Research: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. London: Sage.

- Etherington, K. 2004. Becoming a Reflexive Researcher - Using Our Selves in Research. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Feldman, M. S., and J. Almquist. 2012. “Analyzing the implicit in stories.” In Varieties of Narrative Analysis, edited by J. A. Holstein and I. F. Gubrium, 207–228. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Floyd, A., and L. Arthur. 2012. “Researching from Within: External and Internal Ethical Engagement.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 35 (2): 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2012.670481.

- Flynn, S. V., and L. L. Black. 2013. “Altruism–Self-interest Archetypes: A Paradigmatic Narrative of Counseling Professionals.” The Professional Counselor 3 (2): 54–66. https://doi.org/10.15241/svf.3.2.54.

- Gaudet, S., and D. Robert. 2018. A Journey Through Qualitative Research. From Design to Reporting. Wiley-Blackwell. Hoboken, New Jersey: Blackwell’s.

- Goodson, I. F. 2013. Developing Narrative Theory. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge.

- Goodson, I., G. Biesta, M. Tedder, and N. Adair. 2010. Narrative Learning. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge.

- Gray, D. E. 2013. Doing Research in the Real World. London: Sage.

- Halstead, J. M.1996. “Values and values education in schools.” In Values in education and education in values, edited by J. M. Halstead and M. J. Taylor, 3–14. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Holstein, J., and G. Jaber. 2012. Varieties of Narrative Analysis, edited by J. Holstein and J. Gubrium. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Holton, M., and M. Riley. 2014. “Talking on the Move: Place-Based Interviewing with Undergraduate Students.” Area 46 (1): 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12070.

- Iacono, V. L., P. Symonds, and D. H. K. Brown. 2016. “Skype as a Tool for Qualitative Research Interviews.” Sociological Research Online 21 (2): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.3952.

- Jean, C. D., and C. Vera. 2012. “Narrative Inquiry.” In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods, edited by L. M. Given, 542–544. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Josselson, R. 2007. “The Ethical Attitude in Narrative Research: Principles and Practicalities.” In Handbook of Narrative Inquiry, edited by D. J. Clandinin, 537–566, Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

- Kusenbach, M., and D. R. Loseke. 2013. “Bringing the Social Back In: Some Suggestions for the Qualitative Study of Emotions.” Qualitative Sociology Review IX (2): 20–38. https://doi.org/10.18778/1733-8077.09.2.03.

- Kvale, S., and S. Brinkmann. 2009. InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Leggo, C. 2008. “Narrative Inquiry: Attending to the Art of Discourse.” Language and Literacy 10 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.20360/G2SG6Q.

- Lincoln, Y. S., and E. G. Guba. 1985. Naturalist Inquiry. Beverley Hills: Sage.

- Lincoln, Y. S., and E. G. Guba. 1986. “But is It Rigorous? Trustworthiness and Authenticity in Naturalistic Evaluation.” New Directions for Program Evaluation 1986 (30): 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.1427.

- Lincoln, Y. S., S. Lynham, and E. G. Guba. 2018. “Paradigmatic Controversies, Contradictions, and Emerging Confluences.” In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln, 108–151. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Loseke, D. R. 2007. “The Study of Identity as Cultural, Institutional, Organizational and Personal Narratives: Theoretical and Empirical Integrations.” The Sociological Quarterly 48 (4): 661–688. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2007.00096.x.

- Loseke, D. R. 2009. “Examining Emotion as Discourse: Emotion Codes and Presidential Speeches Justifying War.” The Sociological Quarterly 50 (3): 497–524. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2009.01150.x.

- Loseke, D. R. 2012. “The Empirical Analysis of Formula Stories.” In Varieties of Narrative Analysis, edited by J. A. Holstein and F. Gubrium Jaber, 251–272. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Mertens, D.M. 2019. Research and Evaluation in Education and Psychology. 5th ed. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Mishler, E. G. 1986. Research Interviewing: Context and Narrative. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Morgan, C. 2020. “Advice on Remote Oral History Interviewing During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” 6.

- Nasheeda, A., H. Binti Abdullah, S. Eric Krauss, and N. Binti Ahmed. 2019. “Transforming Transcripts into Stories: A Multimethod Approach to Narrative Analysis.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 18:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919856797.

- Ollerenshaw, J. A., and J. W. Creswell. 2002. “Narrative Research: A Comparison of Two Restorying Data Analysis Approaches.” Qualitative Inquiry 8 (3): 329–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778004008003008.

- Palaiologou, I., D. Needham, and T. Male. 2016. Doing Research in Education: Theory and Practice, edited by Ionna Palaiologou, D. Needham, and T. Male. London: Sage.

- Phoenix, A. 2013. “Analysing Narrative Contexts.” In Doing Narrative Research, edited by M. Andrews, C. Squire, and M. Tamboukou, 72–87. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Phoenix, A. 2017. An Introduction to Narrative Methods -. London: Sage Research Methods Video.

- Phoenix, A. 2021. “UCL Institutional Research Information Service (2021).” Accessed June 22, 2022. https://iris.ucl.ac.uk/iris/browse/profile?upi=AAPHO81.

- Reissman, C. 1993. Narrative Analysis. London: Sage.

- Reissman, C. K. 2008. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Ryckman, R. M., and D. M. Houston. 2003. “Value Priorities in American and British Female and Male University Students.” The Journal of Social Psychology 143 (1): 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224540309598435.

- Safford, R. B., and R. B. Safford. 1930. An Introduction to Narrative Writing. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co.

- Saunders, M. N., P. Lewis, A., and Thornhill . 2019. “Understanding Research Philosophy and Approaches to Theory Development.” In Research Methods for Business Students, edited by M. Saunders, P. Lewis, and A. Thornhill, 128–170. Harlow, Essex: Pearson.

- Savin-Baden, M. and C. Howell Major. 2013. Qualitative Research: An Essential Guide to Theory and Practice. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Schermer, J., P. A. Vernon, G. R. Maio, and K. L. Jang. 2011. “A Behavior Genetic Study of the Connection Between Social Values and Personality.” Twin Research and Human Genetics 14 (03): 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1375/twin.14.3.233.

- Schwartz, S. H.1992. “Universals in the Content and Structure of Values: Theoretical Advances and Empirical Tests in 20 Countries.” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 25: 1–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60281-6.

- Schwartz S H. (2006). Basic human values: Theory, measurement, and applications. Revue Française de Sociologie, 47(4), 929–968. 10.3917/rfs.474.0929

- Schwartz, S. H., and A. Bardi. 2001. “Value Hierarchies Across Cultures: Taking a Similarities Perspective.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 32 (3): 268–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022101032003002.

- Schwartz, S. H., and W. Bilsky. 1987. “Toward a Universal Psychological Structure of Human Values.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 53 (3): 550–562. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.53.3.550.

- Schwartz, S. H., J. Cieciuch, M. Vecchione, E. Davidov, R. Fischer, C. Beierlein, A. Ramos, et al. 2012. “Refining the Theory of Basic Individual Values.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 103 (4): 663–688. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029393.

- Scott, P. 2021. Retreat or Resolution? Tackling the Crisis of Mass Higher Education. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Seemiller, C., and M. Grace. 2016. Generation Z Goes to College. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Seemiller, C., and M. Grace. 2017. “Generation Z: Educating and Engaging the Next Generation of Students.” About Campus 22 (3): 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/abc.21293.

- Tight, M. 2018. Higher Education Research: The Developing Field. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Tight, M. 2019. “Student Retention and Engagement in Higher Education.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2019.1576860.

- Zorn, R.L. 2017 Coming in 2017: A new generation of graduate students - the z generation College & University 92 1 61–63 files/131/Zorn

Appendix A:

Schwartz, S.H. (Citation2006) Basic human values: Theory, measurement and applications. Revue Francaise de Sociologie, 47 (4).